The presence of vineyards at Passy is documented back to the Middle Ages. Convents (Les Minimes and Sainte-Geneviève) took advantage of the sunny limestone hills to cultivate vineyards. After the Revolution, the production of wine continued for consumption by Parisians who, to avoid taxes, came to drink onsite at proletarian cabarets, known as guinguettes. From the middle of the 19th century, diseases of the vine arrived from America (Oidium, mildew and phylloxera), destroying most of these vineyards; increasing urbanisation made short work of the remainder. Today, only the rue des Vignes and the rue Vineuse recall that Passy, now one of the western districts of Paris proper, was once a village devoted to winemaking.

Contemporary with the first novels of Balzac, this painting shows the dome of the Invalides behind the undeveloped plain of Grenelle. The surroundings of Passy were entirely rural: the expansion of Paris to the west had not yet begun.

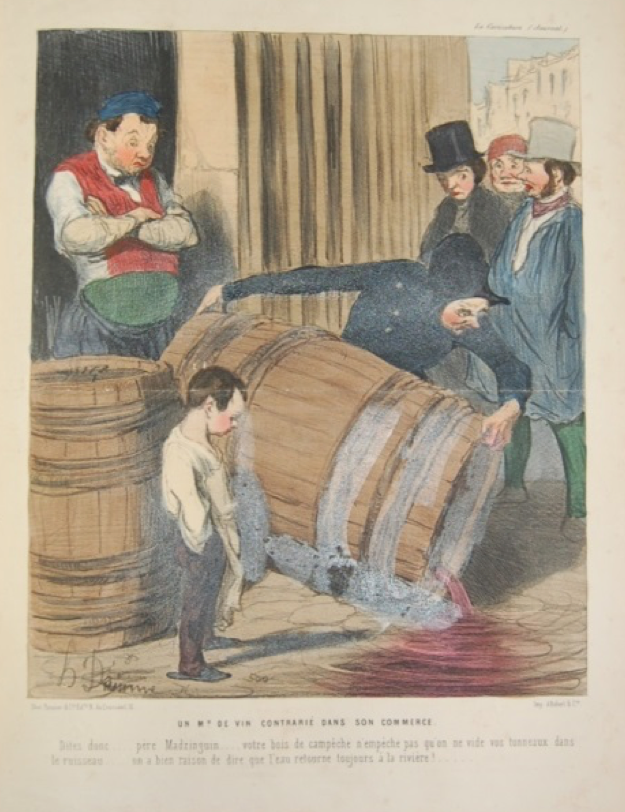

Soldiers of the National Guard empty the contents of a wine barrel into the street, under the sarcastic gaze of a street urchin who remarks: “Hey…Father Madzinguin…Your Campeche wood doesn’t stop them them dumping your barrels in the stream… People are right to say that water always returns to the river!’ This comment condemns the practice of ‘mouillage”, which involved adding water to wine, then using dye to give it a bright red colour, for example the dye made from campeche, or bloodwood, a small tree from the Yucatan. The cost of wine, which was heavily taxed, prompted rampant cheating during the 19th century. Some ‘wine’ contained no grapes at all, a fraud made possible by advances in chemistry and encouraged by a lack of discernment among consumers. It was reported that in 1842, a year before this print appeared, there were 90 fake wine producers convicted in Paris!

In 1842, Balzac published Un début dans la vie (A Start in Life) a novel that begins in the carriage providing transport between Paris and l’Isle-Adam. Several travellers engage in a round of one-upmanship, boasting in front of a young man simple enough to swallow their tales. A notary’s clerk passed himself off as an officer of the pasha of Janina and, when the coach stopped at an inn, he offered everyone a glass of wine from Alicante, which he described in the following terms:

‘“It is all the better,’ said Georges. “because it comes from Bercy. I’ve been to Alicante myself, and I know that this wine no more resembles what is made there than my arm is like a windmill. Our made-up wines are a great deal better than the natural ones in their own country.”’

(translation by Katharine Prescott Wormley, 2010)

The Pasha of Janina: The Pasha of Janina was a celebrated military leader who held sway in what is now Albania until 1822. His tragic end is alluded to by Alexandre Dumas in his novel, The Count of Monte Cristo.

Bercy was a village to the east of Paris where barrels of wine from the provinces destined for Paris were stored.