The Conciergerie, The Châtelet, Saint-Lazare, La Force, Sainte-Pélagie, La Roquette, these names evoque nothing to the strolling passer-by in 21stcentury Paris. But at the time when Balzac was describing Paris, they would cause a shudder. All were prisons.

Whether massive towers and fortresses from the Ancien Régime or buildings specially built for the purpose, prisons received a tremendous flow of people incarcerated for a broad variety of reasons. Alongside assassins and thieves were prostitutes, runaways, beggars, debtors and the mentally ill. Balzac himself was imprisoned for refusing to serve in the National Guard. The facility where he was held bore a most peculiar name: the hôtel des haricots, or ‘bean hotel’.

“Another thing worth noting: the world of prostitutes, thieves, and murders of the galleys and the prisons forms a population of about sixty to eighty thousand souls, men

Honoré de Balzac, Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes, 1847 (Translation James Waring)

In this era, a person arrested on the street would begin their detention with a short stay at the Police Headquarters’ depot, a strangely neutral site packed with the motley crowd of detainees of all stripes. Then a trial, and the condemned was transferred to one of the various Paris prisons, each one possessing its own ‘specialism’: women went to Saint-Lazare, minors to La Roquette. For common offenses, sentences might right from a few months to several years. For other more serious and political crimes punishments consisted of the bagne(penal colony) or execution.

‘What a duel is that between justice and arbitrary wills on one side and the hulks [Le Bagne] and cunning on the other! The hulks—symbolical of that daring which throws off calculation and reflection, which avails itself of any means, which has none of the hypocrisy of high-handed justice, but is the hideous outcome of the starving stomach—the swift and bloodthirsty pretext of hunger. Is it not attack as against self-protection, theft as against property? The terrible quarrel between the social state and the natural

Honoré de Balzac, Splendeurs et misères des

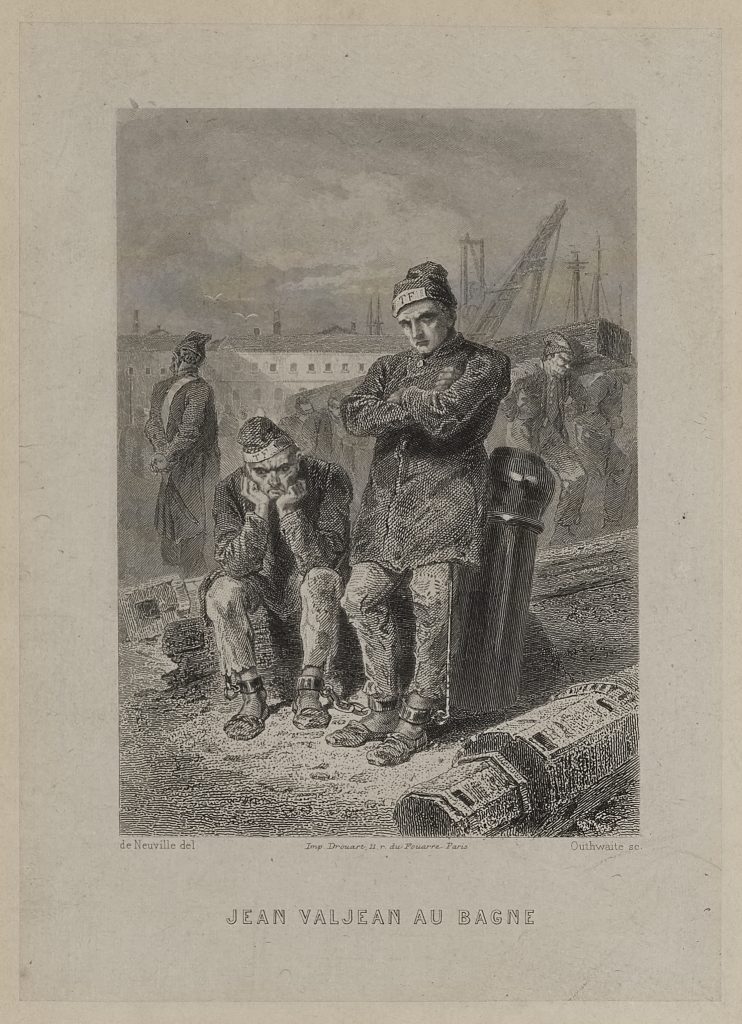

The penal colony was a different world, with its own hardships and rules. Rules that one might follow, be subjected to, or inflict on others. The convict wore irons so heavy they altered his gait forever, he was exiled in the most hostile of environments; he was humiliated in the eyes of the people, who would gaze with morbid curiosity on the chained-up ‘monsters’ waiting to be sent away; and lastly, he lived with constant and perpetual violence as the only strategy for survival. The convict was forced to become hard, resign-himself or die. Few escaped the bagne, and sentences were long, each year an interminable stretch. Successful fugitives from the penal colonies made magnificently deep and complex novelistic heroes. Hugo’s Jean Valjean, Balzac’s Vautrin, in equal measure flamboyant and wicked, desperate to find redemption or vengeance and perpetually fleeing their past as convicts, which could never be fully expunged.