‘With what incumbrances one travels! It is not in the right harmony of things that I should have a hat-box, a secretary, a dressing-case, a trunk, a portmanteau, and a valet always following me. […] But what would Thoreau have said to my hat-box! Or Emerson to the size of my trunk, which is Cyclopean! But I can’t travel without Balzac and Gautier, and they take up so much room […]’

Oscar Wilde, letter to Julia Ward Howe, 6 July 1882

It was not necessary to await the end of the 19thcentury, nor the extravagant Oscar Wilde to find unconditional fans of Balzac. As soon as they were published, his novels elicited strong reactions, and letters to the editor from readers, both male and female, poured in to the newspapers publishing them. Shortly after the author’s death, a new generation of writers began to draw on the master’s work to bring about a renewal of literature.

The times tended to realism, and Balzac was considered a pioneer. With his ability to describe mankind and social type with all they held of the real, the ugly and the grotesque but true, he influenced authors throughout Europe. Dostoyevsky, Maupassant, Alphonse Daudet and more never veered from the legacy of Balzac’s social novel.

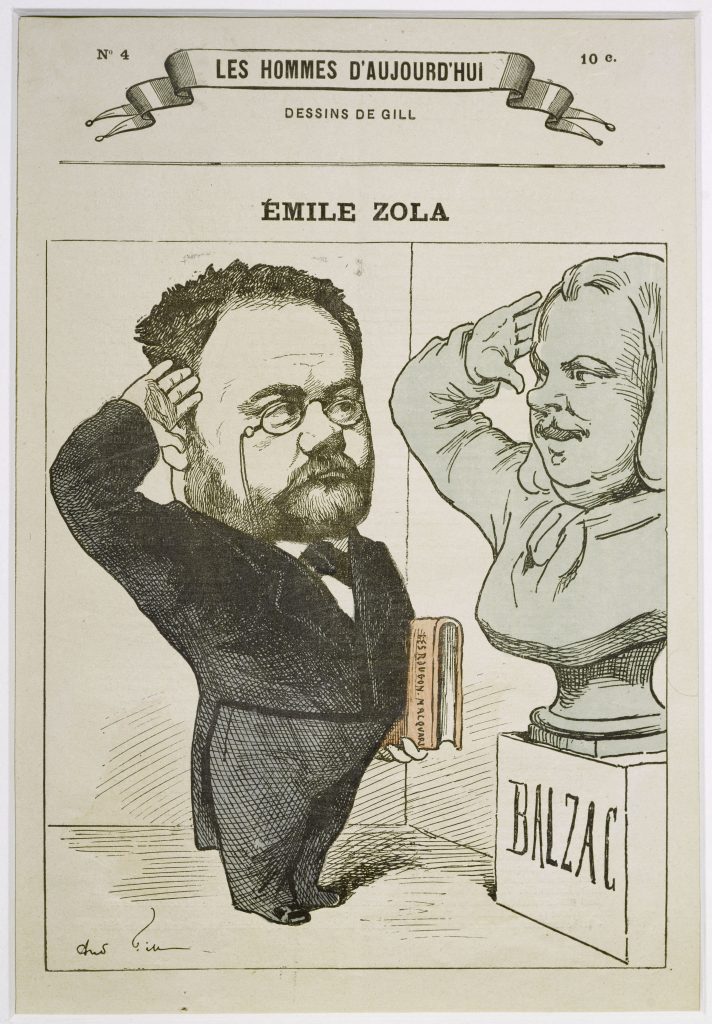

But the author most often described as the heir to Balzac is Émile Zola.

‘Balzac’s true glory is […] in the profound humanity of his creation. Other of our writers have written with more exactitude and brilliance or brought to bear a more balanced

Émile Zola, ‘Balzac,’LeFigaro, 11 April 1880.

Via a cycle of novels, Les Rougon-Macquart, Zola narrates the history of several lives, some of which are intertwined. He weaves into his stories the scientific discoveries of his time, changes in daily life both urban and rural, seeking always to portray the truth of his era. Like Balzac, the realism of his novels owes much to the care with which de describes social conditions and his influence on the characters. But, while Zola takes the exercise to the point of systematisation, Balzac, before him, allowed La Comédie humaineto take shape gradually, a bit like an organic being; a mere observer, he depicted the mediocre and average with delectation, choosing neither to judge nor to tinge with moral sentiment the tales he sketched from life.