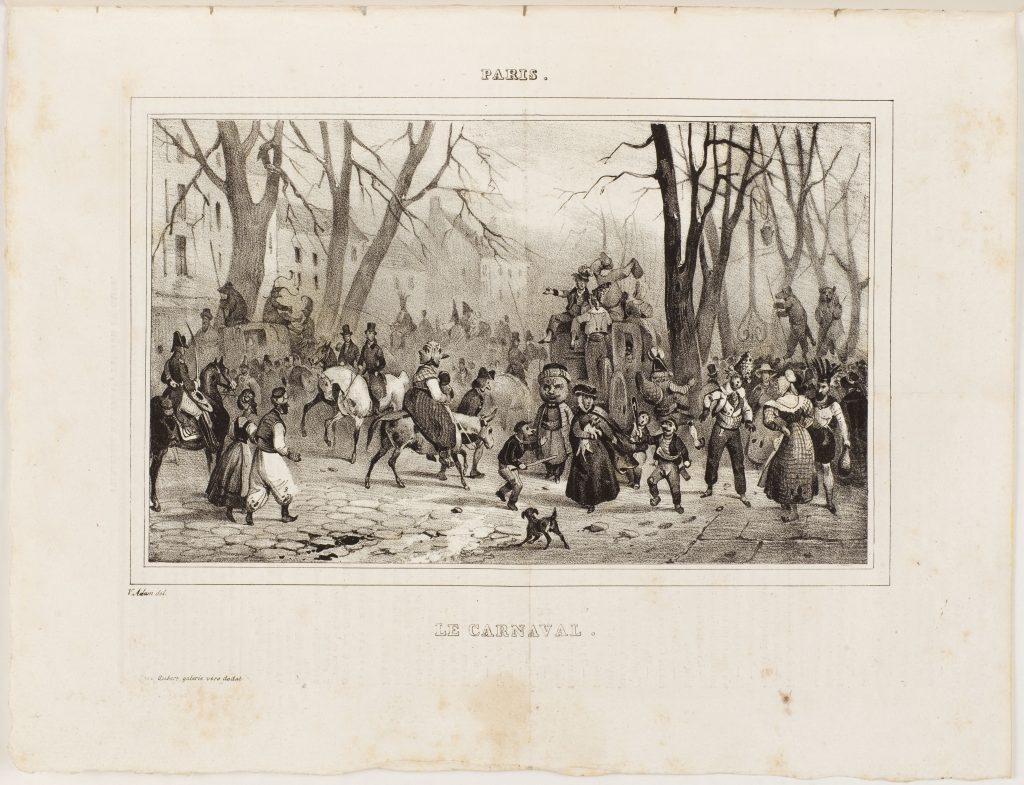

Inaugurated by Napoleon I in 1805, Carnival in Paris opened with the procession of the fattened bull, which was selected in its pasture and paraded through the city, followed by a crowd wearing masks and disguises in which the daintiest of women’s costumes were interspersed with savages and débardeurs (stevedores). Aristocrats rubbed elbows with students, lawyers and blue-collar working girls, both during these parades and at the festive balls. Evenings during Carnival ended in costume balls, after which the masked assembly would leave the various balls to drink and sup at home, in taverns or, in the case of the wealthiest, at the capital’s great restaurants. While the tradition has all but disappeared, Carnival in Paris was once as famous as that of Rio de Janiero is today.

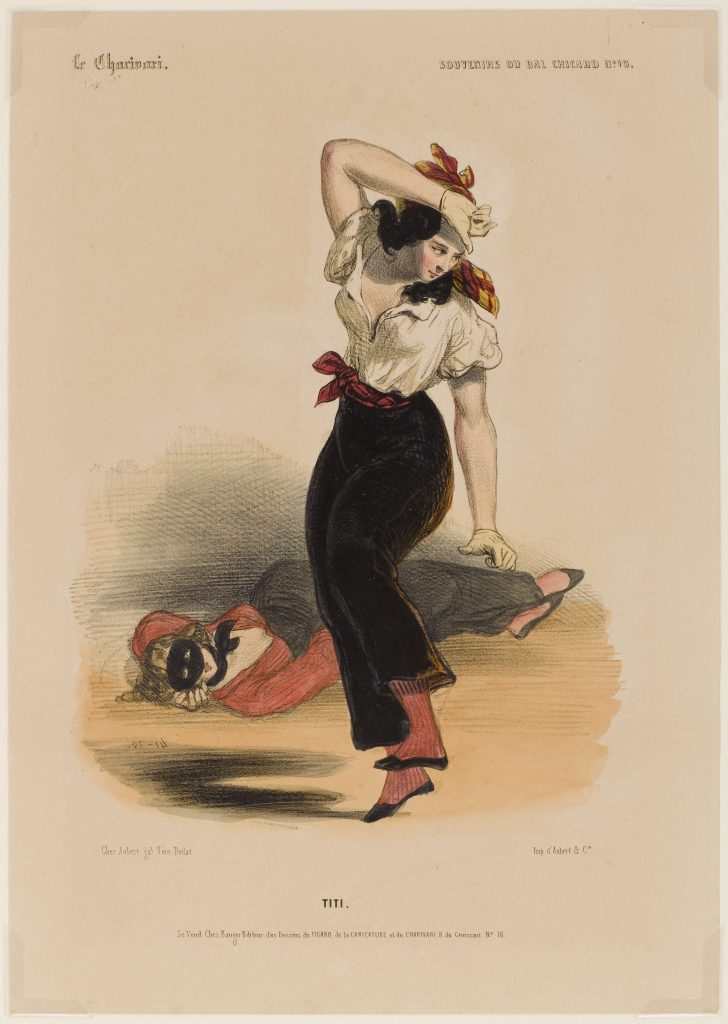

A young lady dressed as a débardeur (stevedore). This disguise highlighted parts of the body concealed by everyday attire, which was one reason for its popularity, but also caused a number of arrests each year, following dance moves considered too suggestive by the police force charged with maintaining decorum at these balls.

‘Everyone knows that since 1830 the carnival in Paris has undergone a transformation which has made it European, and far more burlesque and otherwise lively than the late Carnival of Venice. Is it that the diminishing fortunes of the present time have led Parisians to invent a way of amusing themselves collectively, as for instance at their clubs, where they hold salons without hostesses and without manners, but very cheaply? However this may be, the month of March was prodigal of balls, at which dancing, joking, coarse fun, excitement, grotesque figures, and the sharp satire of Parisian wit, produced extravagant effects. These carnival follies had their special Pandemonium in the rue Saint-Honoré and their Napoleon in Musard, a small man born expressly to lead an orchestra as noisy as the disorderly audience, and to set the time for the galop, that witches’ dance, which was one of Auber’s triumphs, for it did not really take form or poesy till the grand galop in “Gustave” was given to the world.’

Honoré de Balzac, La Fausse Maîtresse, 1841 (Translation by Katharine Prescott Wormeley)

This print depicts the parade that officially opens the Carnival period, wending along the Parisian boulevards according to an itinerary carefully determined by the municipal authorities. In the foreground, boys wielding wooden bats draw rats in chalk on the dark skirts of a passer-by who has imprudently joined the parade without a disguise.

Index:

Débardeurs: name given to the stevedores who brought shipments of wood along the Seine to Paris. The débardeur was readily recognisable by his wide pants, open shirt and flannel belt knotted at the waist. This costume, which was most convenient for dancing, was very popular among young women during the 1830s and 1840s.

Carnival: Period of rejoicing preceding Lent in the Catholic faith from Epiphany to Ash Wednesday. Carnival is also associated with the masquerades and festivities that took place during this time.