L’Histoire Naturelle, a giant encyclopaedia compiling every species of animal known to man at the end of the 18thcentury, was the achievement of a team that included naturalists, biologists and illustrators under the leadership of an exceptional man: Buffon. His classification of species and anatomical comparisons were to provide the basis of modern biology. His followers, such as Cuvier, Geoffroy-Saint-Hilaire and Darwin, would rely on this bedrock of knowledge to develop their theories of evolution.

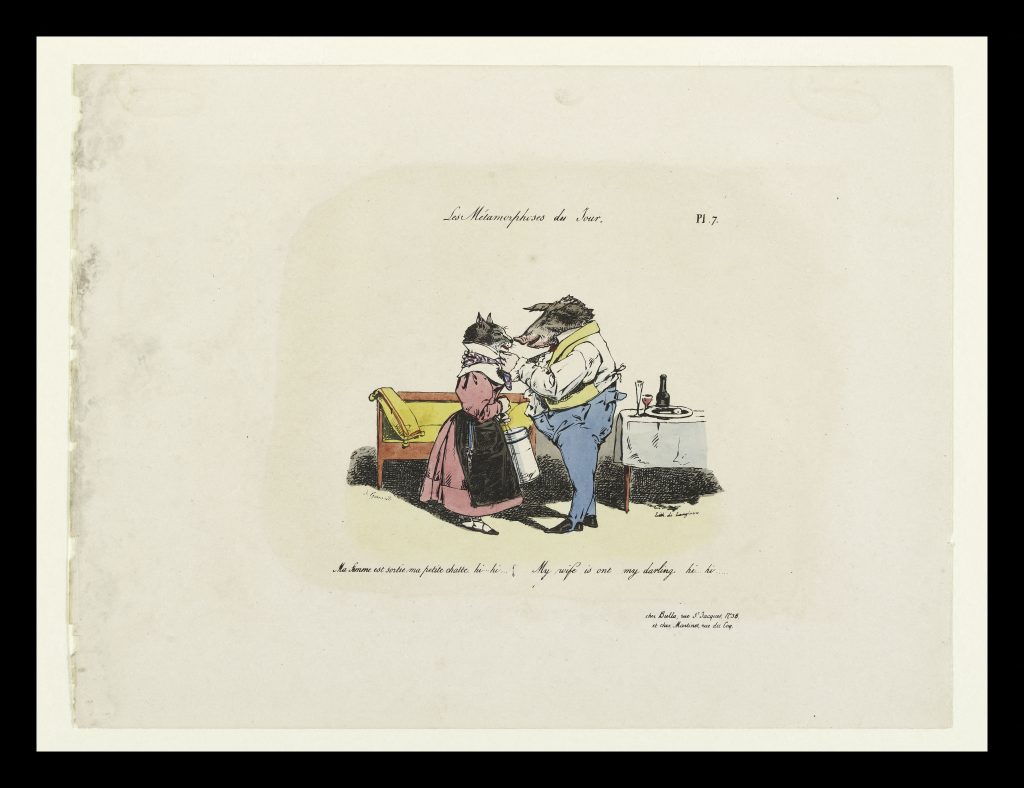

Observing, recording, describing and classifying: writers were by no means indifferent to the new lens through which the world was seen, Balzac especially. His Comédie humaine is not only a collection of novels in which recurring characters intersect, it is a much more ambition project. It was to distinguish and classify the social species, to describe humanity’s every facet, interacting with the specific biotope that was the society of his era. Thus are the soldier, worker, poet and priest like the lion, the ass, the crow or the ewe, living and dying as distinct species governed by the laws of their natural habitats. Balzac adopts Buffon’s principles for describing species and Cuvier’s method for classifying them. His oeuvre is therefore divided into three parts: the Études de mœurs, the Études philosophiquesand the Études analytiques. The various characters in this way become specimens in an encyclopaedia of human society. They flail around, driven by the influence of external and internal stimuli under gaze of the writer wielding a magnifying glass and sharpened pen.

‘Is not Cuvier the great poet of our era? Byron has given admirable expression to certain moral conflicts, but our immortal naturalist has reconstructed past worlds from a few bleached bones; has rebuilt cities, like Cadmus, with monsters’ teeth; has animated forests with all the secrets of zoology gleaned from a piece of coal; has discovered a giant population from the footprints of a mammoth. These forms stand erect, grow large, and fill regions commensurate with their giant size. He treats figures like a poet; a naught set beside a seven by him produces awe.’

Honoré de Balzac, La Peau de Chagrin, 1831 (Translation Ellen Marriage)

‘If Buffon could produce a magnificent work by attempting to represent in a book the whole realm of zoology, was there not room for a work of the same kind on society? But the limits set by nature to the variations of animals have no existence in society. When Buffon describes the lion, he dismisses the lioness with a few phrases; but in society a wife is not always the female of the male. There may be two perfectly dissimilar beings in one household. The wife of a shopkeeper is sometimes worthy of a prince, and the wife of a prince is often worthless compared with the wife of an artisan. The social state has freaks which Nature does not allow herself; it is nature plus society. The description of social species would thus be at least double that of animal species, merely in view of the two sexes. Then, among animals the drama is limited; there is scarcely any confusion; they turn and rend each other–that is all. Men, too, rend each other; but their greater or less intelligence makes the struggle far more complicated. Though some savants do not yet admit that the animal nature flows into human nature through an immense tide of life, the grocer certainly becomes a peer, and the noble sometimes sinks to the lowest social grade. Again, Buffon found that life was extremely simple among animals. Animals have little property, and neither arts nor sciences; while man, by a law that has yet to be sought, has a tendency to express his culture, his thoughts, and his life in everything he appropriates to his use. Though Leuwenhoek, Swammerdam, Spallanzani, Reaumur, Charles Bonnet, Muller, Haller and other patient investigators have shown us how interesting are the habits of animals, those of each kind, are, at least to our eyes, always and in every age alike; whereas the dress, the manners, the speech, the dwelling of a prince, a banker, an artist, a citizen, a priest, and a pauper are absolutely unlike, and change with every phase of civilization.

Honoré de Balzac, Avant-propos (Foreword) à la Comédie Humaine, 1842