‘It’s my folly that is the making of me.’ This was neither the watchword nor the motto, but rather the meaning of life for George ‘Beau’ Brummell (1778-1840), the British figurehead of this singular type. In France, there sprang up around him first the Incroyables and Muscadins, then in the first half of the 19th century, a pride of Lions, followed by a feline host of Tigers, Panthers, Lionesses and lion cubs, all larger-than-life figures breathing the swansong of uncompromising aristocratic resistance to bourgeois utilitarianism and the straightjacket of its increasingly restrictive social conventions.

Ever prepared to bet his life over a scrap of cloth or a word, the dandy overcompensated for some aspect of his personal history. Often from the lower classes, he was an irresistible presence, constantly engaged in self-creation, both surprising and disconcerting; while inducing fear—which gives to grace its zest—the dandy is imbued with a poetic mystery that cannot be pinpointed but invariably convinces through a fascinating elegance. Lacking any instinct of self-preservation, the dandy can play his life on a roll of the dice or with the same sang-froid offer it up to save the world. He heightens desire with his taste for the sulphurous and the abyss, irresistible for the fall he constantly holds at bay. Never does he retreat from nor deny the spectacle that he makes of himself. A member of no particular class, he surpasses them all.

A demi-god close to a work of art, the dandy exists only to leave the common lot of man behind. It is a matter of life and death. His paradox is to constantly amaze, while remaining indifferent to the opinion of others, unless it should guarantee him a bad reputation, generally for good reasons, such as crime, as long as he makes something of it. After all, did not Pierre-François Lacenaire, elegant in every possible respect, take the blood of others as the medium for his art in the end?

An ephemeral creature, the Dandy always dies young, at least figuratively speaking. Futile in the eyes of philistines, this devotee of the Ideal who reeks of ironic pomp would risk wearing thin the veneer of charm, leaving only disdain, cynicism and sententious sarcasm once the proud and lively extravagance of youth ceased to exceed his neurotic need for attention.

Traité de la vie élégante

Paris : La Mode, 2 octobre-6 novembre 1830 (cinq articles)

[Partie] XXXIX

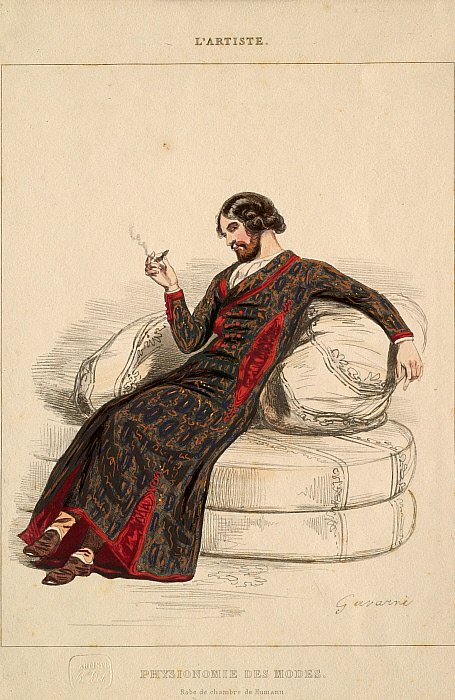

Dandyism is a heresy of elegant life.

“In effect, dandyism is an affectation of fashion. In playing the dandy, a man becomes a piece of furniture for the boudoir, an extremely ingenious mannequin that can sit upon a horse or a couch, that bites or sucks on the end of a walking stick by habit—but a thinking being… never! The man who sees only fashion in fashion is a fool. Elegant living excludes neither thought nor science: it sanctions them. It must learn not only how to enjoy time, but to employ it in accordance with an extremely high order of ideas.

[…]

Do we not all know an amiable egoist who possesses the secret of telling us about himself without overly displeasing us? With him, everything is graceful, fresh, meticulous, even poetic. He makes himself envied. As you share in his interests and pleasures, in his wealth, he seems to feel concern about your lack of fortune. His obligingness, in all his speech, is a sophisticated courtesy. For him, friendship is but a theme whose richness he knows admirably well, and whose modulations he assesses in tune with every person.

His life in imprinted with perpetual personality, by which he obtains forgiveness because of his manners: artistic with artists, old with an old man, a child with children, he captivates without pleasing, for he tells us lies out of self-interest and amuses us through ulterior motives. He looks after us and is affectionate with us because he is bored, and if today we notice that we have been played, tomorrow we shall again go back to be deceived… This man has essential grace.

But thre is a person whose harmonious voice marks his speech with a charm that is equally widespread in his manners. He knows when to speak and when to stay silent, takes a tactful interest in you, employs ony appropriate subjects for conversation; his words are well chosen; his language is pure, his mockery flatters, and his criticism does not offend. Far from being at variance from you with the ignorant self-assurance of a fool, he seems to seek in your company good sense or truth. He does not hold forth any more than he fights; he takes pleasure in leading a discussion that he brings to an end at the right moment. Even-tempered, his manner is affable and pleasant. There is nothing forced about his courtesy, his attentiveness is not the slightest bit servile; he reduces respect to nothing more than a gentle shadow; he never tires you and leaves you feeling pleased with him and with yourself. Led into his sphere through an inexplicable magnetism, you will recall his spirit of good grace imprinted on the things that surround him; everything about him delights the eye and allows you to breathe as if it were the air of your homeland. In private life, this person charms you with an innovent tone. He is unaffected. Never any effort, any excessive display of wealth, any flaunting; his feelings are rendered simply because they are real. He is frank, and never offends another’s pride. He accepts men as God does, forgiving faults and silly ways, understanding every age and never feeling any irritation, because he is tactful enough to anticipate anything. He obliges you to him before consoling, he is loving and cheerful: and so you will love him irresistibly. You take him for a classic example and devote a cult to him.

[…]

This person has divine and concomitant grace.

[…]

This magnetic power is the great aim of elegant life. We must try everything to lay hold of it; but a successful outcome is always difficult, for the cause of success lies within a beautiful soul. Happy are those who exercise it! It is so nice to see everything appeal to us, both in nature and in Men…”

Le Cabinet des Antiques (translation Ellen Marriage)

La Comédie humaine. Œuvres complètes de M. de Balzac

Paris : chez Furne, Dubochet et Cie, Hetzel et Paulin, 1844

7ème Volume, Études de mœurs, tome III des Scènes de la vie de province

“And Chesnel also wrote. The fond flattery to which the unhappy boy was only too well accustomed shone out of every page; and Mlle. Armande seemed to share half of Mme. de Maufrigneuse’s happiness. Thus happy in the approval of his family, the young Count made a spirited beginning in the perilous and costly ways of dandyism. He had five horses–he was moderate–de Marsay had fourteen! He returned the Vidame’s hospitality, even including Blondet in the invitation, as well as de Marsay and Rastignac. The dinner cost five hundred francs, and the noble provincial was feted on the same scale. Victurnien played a good deal, and, for his misfortune, at the fashionable game of whist.

He laid out his days in busy idleness. Every day between twelve and three o’clock he was with the Duchess; afterwards he went to meet her in the Bois de Boulogne and ride beside her carriage. Sometimes the charming couple rode together, but this was early in fine summer mornings. Society, balls, the theatre, and gaiety filled the Count’s evening hours. Everywhere Victurnien made a brilliant figure, everywhere he flung the pearls of his wit broadcast. He gave his opinion on men, affairs, and events in profound sayings; he would have put you in mind of a fruit-tree putting forth all its strength in blossom. He was leading an enervating life wasteful of money, and even yet more wasteful, it may be of a man’s soul; in that life the fairest talents are buried out of sight, the most incorruptible honesty perishes, the best-tempered springs of will are slackened.”

La Peau de chagrin (Translation Ellen Marriage)

La Comédie humaine. Œuvres complètes de M. de Balzac

Paris : chez Furne, Dubochet et Cie, Hetzel et Paulin, 1845

14ème volume, tome I des Études philosophiques

[Première partie :] LE TALISMAN

55. ‘“Yes, cashmere, point d’Alencon, perfumes, gold, silks, luxury, everything that sparkles, everything pleasant, belongs to youth alone.”’

[…]

But does not happiness come from the soul within?” cried Raphael.

It may be so,” Aquilina answered; “but is it nothing to be conscious of admiration and flattery; to triumph over other women, even over the most virtuous, humiliating them before our beauty and our splendor? Not only so; one day of our life is worth ten years of a bourgeoise existence, and so it is all summed up.” “Is not a woman hateful without virtue?” Emile said to Raphael. Euphrasia’s glance was like a viper’s, as she said, with an irony in her voice that cannot be rendered: “Virtue! we leave that to deformity and to ugly women. What would the poor things be without it?”

Illusions perdues. Deuxième partie : Un grand homme de province à Paris

La Comédie humaine. Œuvres complètes de M. de Balzac

Paris : chez Furne, Dubochet et Cie, Hetzel et Paulin, 1843

8ème volume, tome IV des Scènes de la vie de province

“He walked in the lobby, arm in arm with Merlin and Blondet, looking the dandies who had once made merry at his expense between the eyes. Chatelet was under his feet. He clashed glances with de Marsay, Vandenesse, and Manerville, the bucks of that day. And indeed Lucien, beautiful and elegantly arrayed, had caused a discussion in the Marquise d’Espard’s box; Rastignac had paid a long visit, and the Marquise and Mme. de Bargeton put up their opera-glasses at Coralie. Did the sight of Lucien send a pang of regret through Mme. de Bargeton’s heart? This thought was uppermost in the poet’s mind. The longing for revenge aroused in him by the sight of the Corinne of Angouleme was as fierce as on that day when the lady and her cousin had cut him in the Champs-Elysees.

[…]

Lucien was living from hand to mouth, spending his money as fast as he made it, like many another journalist; nor did he give so much as a thought to those periodically recurrent days of reckoning which chequer the life of the bohemian in Paris so sadly. In dress and figure he was a rival for the great dandies of the day. Coralie, like all zealots, loved to adorn her idol. She ruined herself to give her beloved poet the accoutrements which had so stirred his envy in the Garden of the Tuileries. Lucien had wonderful canes, and a charming eyeglass; he had diamond studs, and scarf-rings, and signet-rings, besides an assortment of waistcoats marvelous to behold, and in sufficient number to match every color in a variety of costumes. His transition to the estate of dandy swiftly followed. When he went to the German Minister’s dinner, all the young men regarded him with suppressed envy; yet de Marsay, Vandenesse, Ajuda-Pinto, Maxime de Trailles, Rastignac, Beaudenord, Manerville, and the Duc de Maufrigneuse gave place to none in the kingdom of fashion. Men of fashion are as jealous among themselves as women, and in the same way. Lucien was placed between Mme. de Montcornet and Mme. d’Espard, in whose honor the dinner was given; both ladies overwhelmed him with flatteries.”

Le Député d’Arcis (Translation Katherine Prescott Wormeley)

La Comédie humaine. Œuvres complètes de M. de Balzac

Paris : chez Furne, Dubochet et Cie, Hetzel et Paulin, 185.

18ème volume : Roman inachevé. (Rattaché à La Comédie humaine, édition post-mortem dite du Furne corrigé)

PART I: THE ELECTION

CHAPITRE XII: The Salon of Madame d’Espinard

“De Marsay dead, Comte Maxime de Trailles had fallen back into his former state of existence. He went to the baths every year and gambled; he returned to Paris for the winter; but, though he received some large sums from the depths of certain niggardly coffers, that sort of half-pay to a daring man kept for use at any moment and possessing many secrets of the art of diplomacy, was insufficient for the dissipations of a life as splendid as that of the king of dandies, the tyrant of several Parisian clubs. Consequently Comte Maxime was often uneasy about matters financial. Possessing no property, he had never been able to consolidate his position by being made a deputy; also, having no ostensible functions, it was impossible for him to hold a knife at the throat of any minister to compel his nomination as peer of France. At the present moment he saw that Time was getting the better of him; for his lavish dissipations were beginning to wear upon his person, as they had already worn out his divers fortunes. In spite of his splendid exterior, he knew himself, and could not be deceived about that self. He intended to “make an end”—to marry. “

Histoire des Treize. II La Duchesse de langeais

La Comédie humaine. Œuvres complètes de M. de Balzac

Paris :chez Furne, Dubochet et Cie, Hetzel et Paulin, 1843

9ème volume, tome I des Scènes de la vie parisienne

CHAPTER II

LOVE IN THE PARISH OF SAINT THOMAS AQUINAS

“The Duchess, struck from the first by the appearance of this romantic figure, was even more impressed when she learned that this was that Marquis de Montriveau of whom she had dreamed during the night. She had been with him among the hot desert sands, he had been the companion of her nightmare wanderings; for such a woman was not this a delightful presage of a new interest in her life? And never was a man’s exterior a better exponent of his character; never were curious glances so well justified. The principal characteristic of his great, square-hewn head was the thick, luxuriant black hair which framed his face, and gave him a strikingly close resemblance to General Kleber; and the likeness still held good in the vigorous forehead, in the outlines of his face, the quiet fearlessness of his eyes, and a kind of fiery vehemence expressed by strongly marked features. He was short, deep-chested, and muscular as a lion. There was something of the despot about him, and an indescribable suggestion of the security of strength in his gait, bearing, and slightest movements. He seemed to know that his will was irresistible, perhaps because he wished for nothing unjust. And yet, like all really strong men, he was mild of speech, simple in his manners, and kindly natured; although it seemed as if, in the stress of a great crisis, all these finer qualities must disappear, and the man would show himself implacable, unshaken in his resolve, terrific in action. There was a certain drawing in of the inner line of the lips which, to a close observer, indicated an ironical bent.“