In February 1830, the first performance of the play Hernani was the object of a political and literary conspiracy. Victor Hugo’s admirers joined forces to defend the play, in a battle that the participants’ accounts—and especially that of Théophile Gautier—would immortalise in epic form. The ‘Battle of Hernani’ did not put an end to theatre in the Classical style, but it marked the beginnings of Romantic drama.

The particularly vivid and colourful stories told by Hernani‘s supporters gave this evening such a grandiose aspect that it became the customary to present it as a Homeric battle, and a decisive landmark in the history of French theatre. Subsequent paintings and films further contributed to the development of this legend.

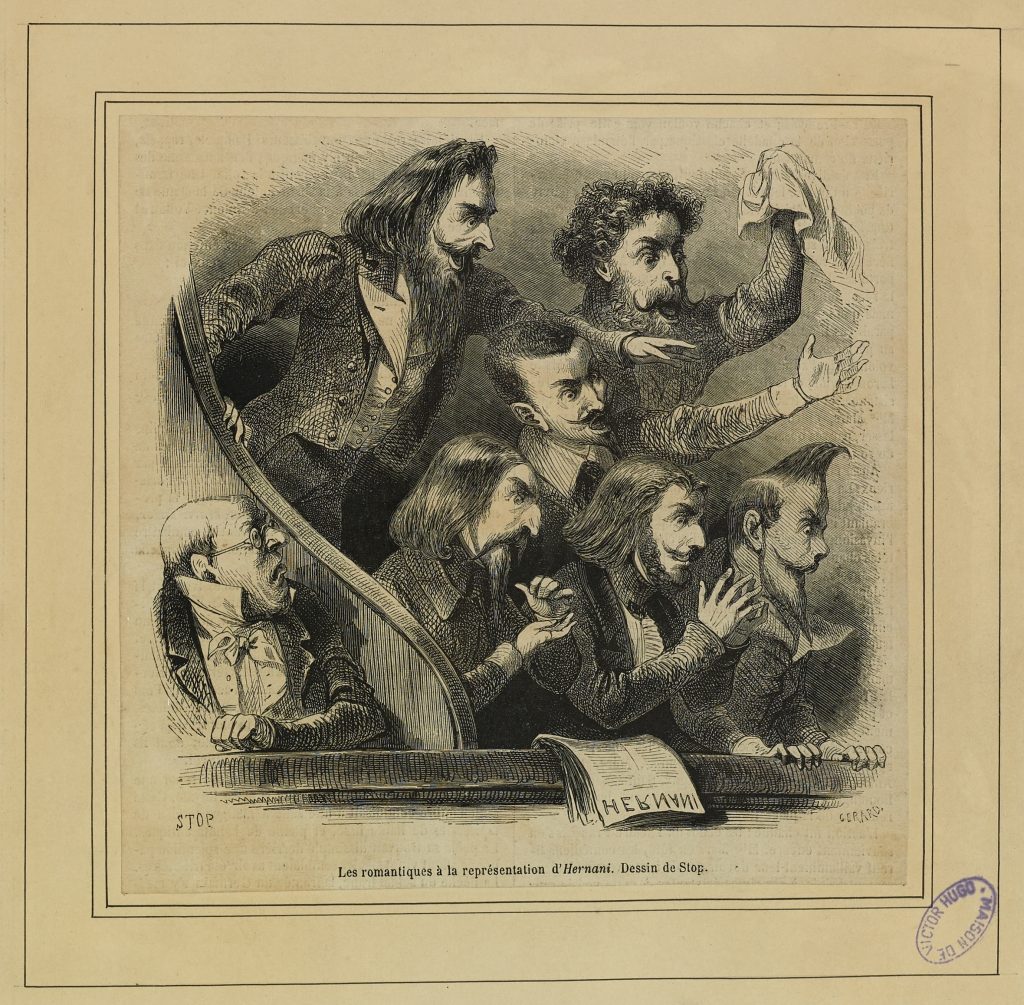

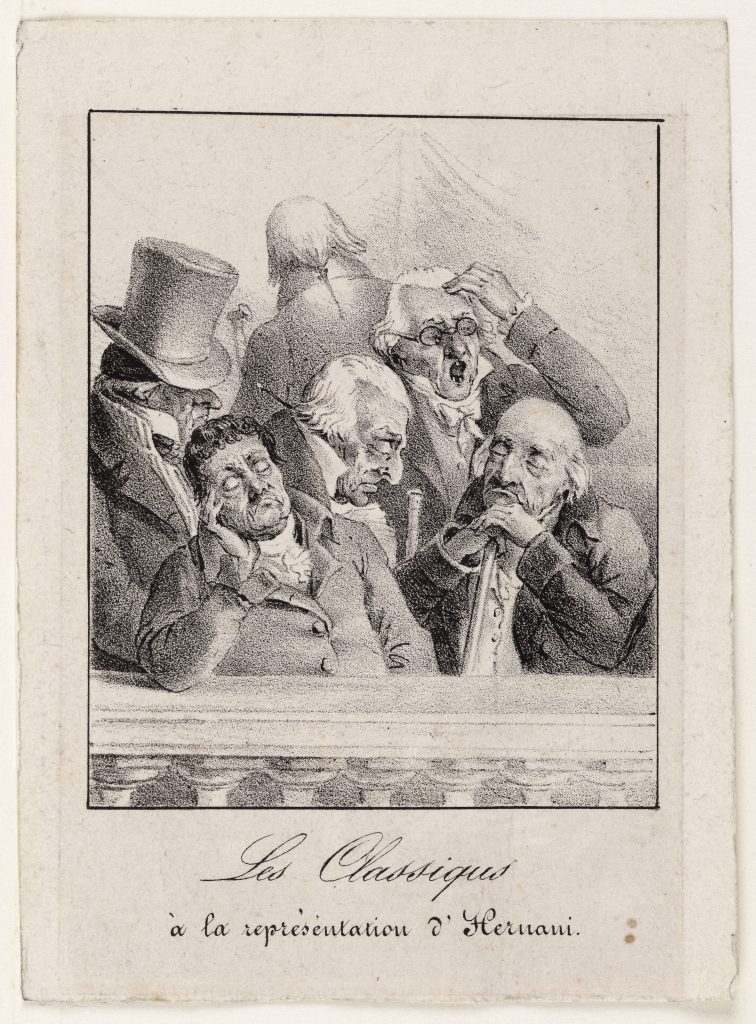

While the challenge to the dogmas of theatrical classicism dates back to the 17th century, the great uproar surrounding controversial plays began only a few years before the French Revolution. That surrounding Hernani stirred humourists who looked at the contrast between Victor Hugo’s young, bearded, virulent supporters and the supporters of a more classic conception of the drama, portrayed as old, half-asleep, and hiding their baldness under wigs.

“February 25, 1830! That date stands out in my past in letters of fire; it is that of the first performance of Hernani. That one evening moulded my whole life. It was then I felt the impulse which yet drives me on, though so many years have elapsed, and which will keep me going to the end of my career. Though much time has gone by, I still feel the same sensation of dazzling beauty; the enthusiasm of my youth has not waned, and whenever I hear the magic sound of the horn, I prick up my ears like an old war-horse ready to rush into battle again.

[…]

The smaller fry of the press of that day and polemical writers took pleasure in describing as a rabble of sordid roughs these young fellows, all of whom belonged to good families, who were well educated, well bred, crazy about art and poetry, some of them writers, some painters, some composers, others sculptors or architects or critics, or in some way busied with things literary, It was not Attila’s filthy, fierce, unkempt, ignorant Huns that were encamped in front of the Theatre-Français, but the knights of the future, the champions of thought, the defenders of the freedom of art; and they were handsome, free, and young. They had hair, that goes without saying, for a man cannot be born with a wig on, and plenty of hair, falling in soft and shining curls, for they combed it carefully. Some wore small mustaches and others full beards.“

Théophile Gautier, A History of Romanticism, 1874 (published posthumously) (Translation Professor F. C. De Sumichrast)

The controversy perpetuated by journalists who were friends of Victor Hugo found its way into the newspapers: everything was a pretext for supporting the new theatre. Even gastronomy magazines got involved!

“It is not that the gourmet should avoid this Hernani, on which the Academy, the censors and the members of the Caveau Classique wish to heap all the whistles that did justice to their own works; on the contrary, Mr Victor Hugo, creator of the Romantic school, has worked to give us new pleasures, new sensations. The gourmet must be devoted to the pleasures of body and mind, according to the idea that the senses are to life what a keyboard is to music. It is not enough for the keyboard to be harmonious – sounds must be artfully drawn from it. Likewise, the gourmet cannot remain indifferent to Victor Hugo’s original merit. Let literary prudery say that Hernani is a composition that offends taste!“

Anonymous, ‘Digestion dramatique’, Le Gastronome journal universel du goût, 14 March 1830

Not all writers admired this new theatre. Balzac left a rather virulent criticism of this play, whose excesses he did not especially appreciate. This did not prevent him from maintaining a very courteous relationship with Victor Hugo.

“We summarise our review by saying that all the elements in this piece are tired; the subject is inadmissible, even if based on true events, because not all adventures should be dramatised; the characters are false; the conduct of the characters contrary to common sense; and in a few years, the admirers of this first instalment of the trilogy that Mr Victor Hugo promises us will be very surprised that they were so passionate about Hernani. To us, the author seems thus far to be a better prose writer than a poet, and more of a poet than a playwright. Mr Victor Hugo will only ever meet a hint of the natural by chance and, in the absence of focussed, conscientious work and a docile appreciation for the advice of stern friends, the stage is forbidden him. Between the preface of Cromwell and the drama of Hernani, there is a huge rift. Hernani would have provided at most the subject of a ballad.“

Honoré de Balzac, “Hernani, drame nouveau, par M. Victor Hugo. Deuxième et dernier article”, Feuilleton des journaux politiques, 7 April 1830.

Romantic: Romanticism is a cultural movement that spread across Europe in the late 18th and early 19th century, but with so many forms, in so many different areas, that it is impossible to precisely define it. It is often contrasted with Classicism, which was based on respect for rules and tradition, on knowledge and rational reflection. Romanticism came to be defined by the expression of sensitivity: emotion and imagination dominate, and artists seek above all to convey their feelings to spectators or readers. The heart prevails over reason. In France, the artists considered to be the best representatives of Romanticism include François-René de Chateaubriand, Victor Hugo, Eugène Delacroix, Hector Berlioz and Antoine-Louis Barye.