Freedom of the press in the first half of the 19th century exhibits a history that parallels the various regimes.

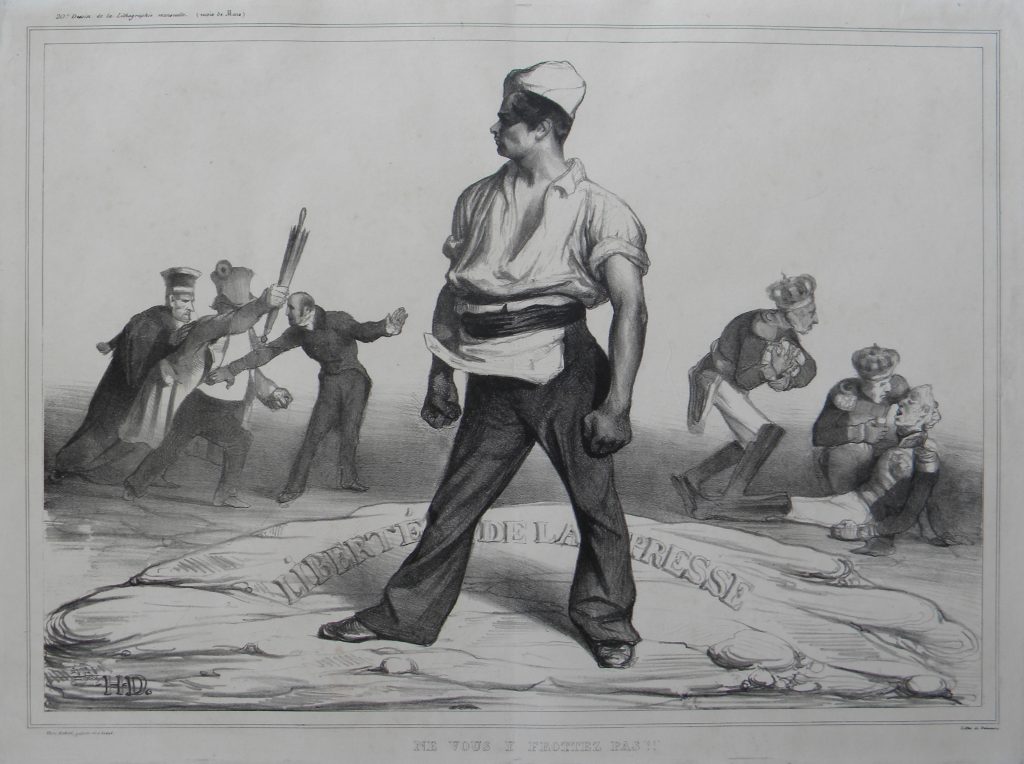

In 1789, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizens proclaimed freedom of the press to be a natural and incontrovertible right, one which was promptly stifled by the Convention, the Directoire and then the Empire. The Restauration proved less severe, however, on 25 July of 1830, Charles X decided to reinstate censorship; a few days later, the uprising known as the ‘Trois Gloirieuses’ (Three days of glory, namely 27, 28 and 29 July 1830) forced him to abdicate. His more liberal successor, Louis-Philippe, first gave journalists free rein entirely, leading to an explosion of periodicals. Satirical illustrated journals such as La Caricature or Le Charivari met with tremendous success, and political cartoons flourished tremendously.

But in 1835, the anarchist Fieschi committed an especially murderous attack on the King, who had already been the target of several assassination plots. Repressive laws were passed to muzzle the press. Many periodicals disappeared or were obliged to reinvent themselves, while cartoonists turned to social caricature. The press would regain its freedom only in 1881, subject to a variety of restrictive clauses.

The press would regain its freedom only in 1881, subject to a variety of restrictive clauses.

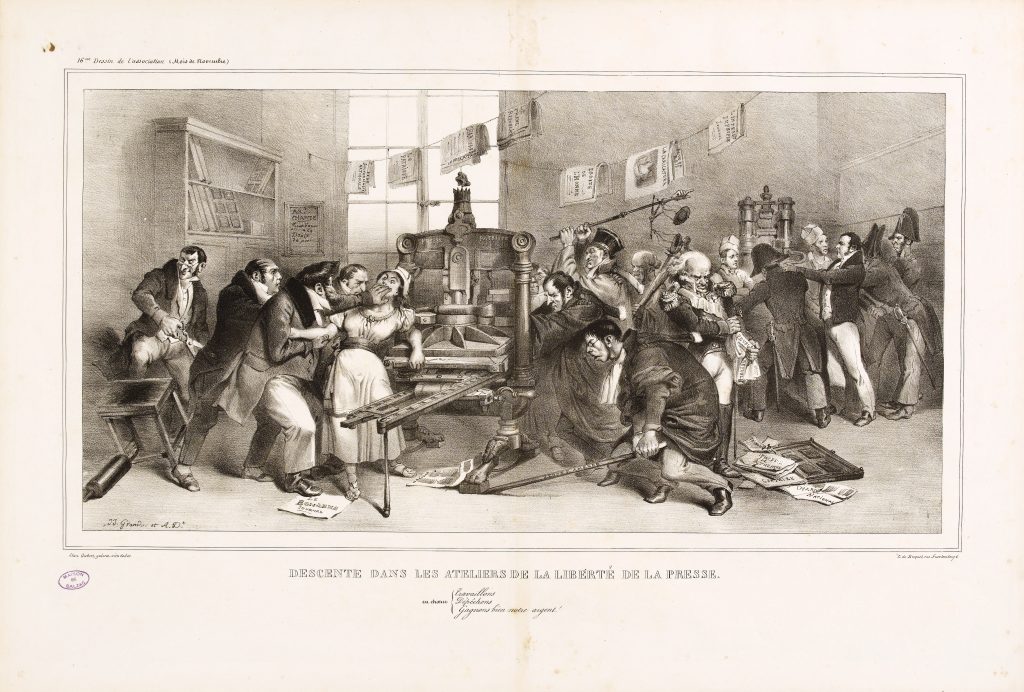

While censorship was officially abolished during the first years of Louis-Philippe’s reign, the State lost no time using fines and lawsuits to crack down on opposition publications. In turn, these papers used their bullying to advertise their significance to readers, as in this striking engraving by Grandville.