More courted than courtly, the Courtesan, in what she deigns to show and what she represents at the height of her position, has but one motto: ‘Ask for nothing, achieve everything.’ Unlike the Dandy, who, despite—or because of his ostentatious refinement is prone to putting himself forward—he literally ‘pro-stitutes’ himself, the Lioness, to call her by her other name, is capable of any cruelty if there be something in it for her, but remains all the more reserved as her price is set by her rarity.

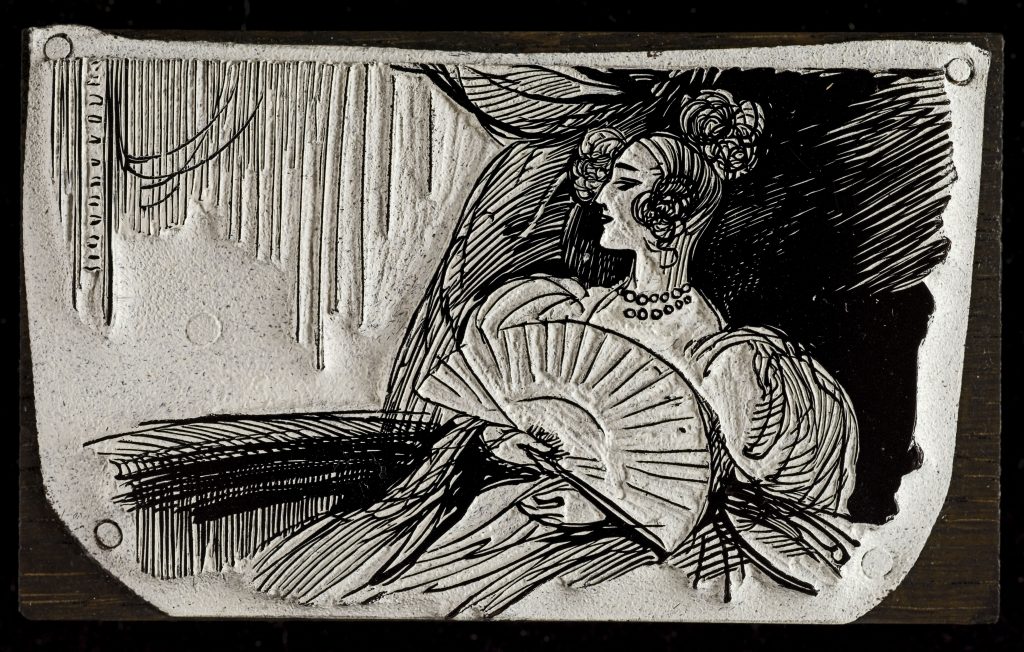

Contrary to the Panther, who reigns over the Boulevards without being a streetwalker, the courtesan does no more than cross them as she makes her way from one Salon to another, or from a box at the opera to another at the theatre, meet environments for her magnificence, always visible but only from a distance. The only virtue she may be said to have is a glacial logic and abhorrence for any social misstep. She cultivates restraint by cold calculation; everything about her is smoke and mirrors, she perpetually promises a portion of the sublime, the ideal, a fugitive but immortal grace, the possibility of everything, always out of reach, because she well knows that keeping something back is essential to maintaining the power to be maintained. For the courtesan accumulates, but with a veneer of respectability that allows her be considered a powerful woman whose prerogatives no one would begin to question.

The courtesan does not go after hearts (unless they be of gold), nor souls, but rather positions, power and wealth, both in terms of investments and profits. Her value lies in her majestic distinction, a sublime token for those who gather in her wake. A rare trophy to be fought for, she reigns over the vanities she assembles at her court, dismissing whomever is guilty of lacking good credit, of any sort. Vestal of her own social apotheosis, sometimes the result of truly monstrous efforts, she knows that any real human feeling is forbidden, lest she fall from grace. To love would mean betraying herself, melting away and doubtless dying altogether. Courted by men, she is sometimes loved by a woman, but shame on her who falls for some handsome poet or penniless fop.

Pragmatic from the top of her cool head to the bottom of her frozen heart, she calculates the utility of her choices with every instant, her sometimes wretched origins ever reminding her of the precariousness of her existence. Her only salvation is the fascination she provokes. She simulates and stages her own life in that of others, sharp-witted, even cultured, enamoured of the arts as part of her pursuit of perfection—insofar as they contribute to her mise-en-scene.

Like the Dandy, the courtesan creates her physical appearance, it is the captivating ornament that channels the energy needed to sustain the joys of illusion, at the going rate for gold and diamonds. Keeping up appearances has its price, just like salvation.