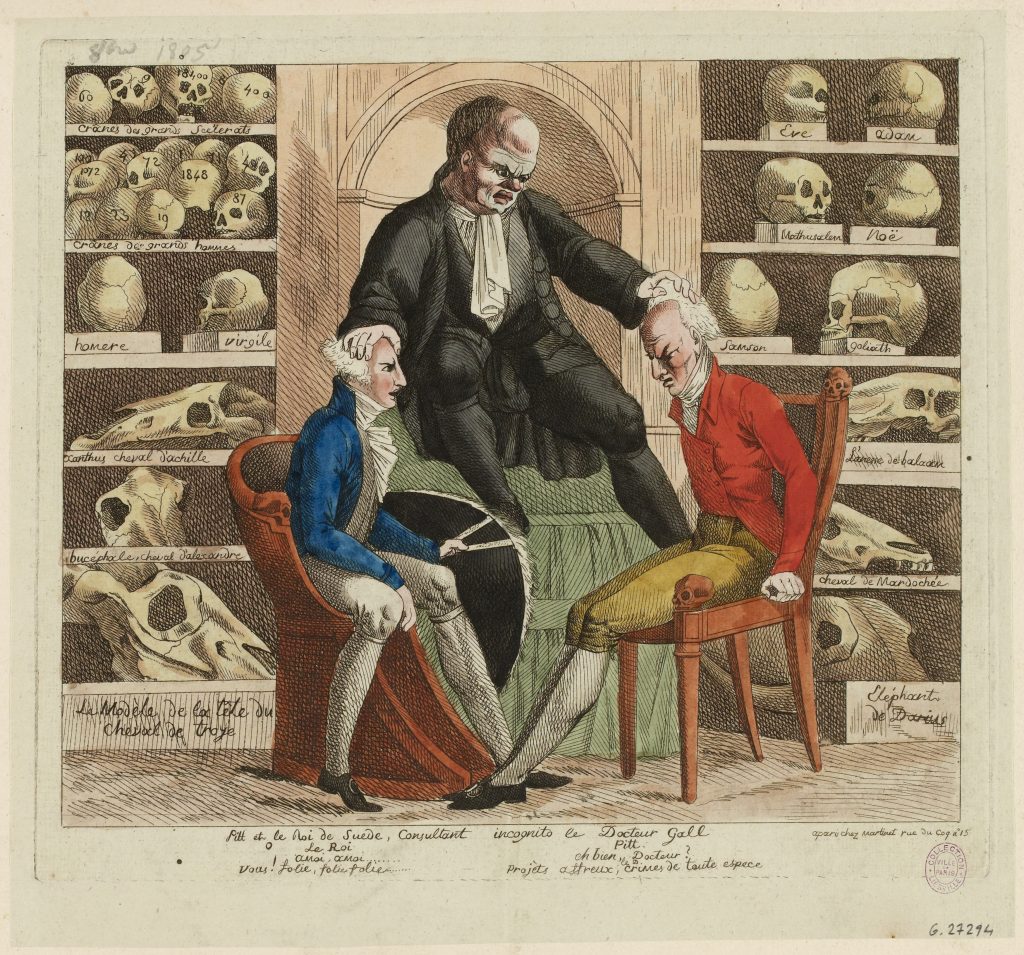

With several hundred enthusiasts among the doctors working in asylums and prisons, phrenology was highly fashionable in the first half of the 19thcentury. This theory, based on empirical observation, was developed in France by Dr Gall. It consisted in feeling, measuring and collecting casts of skulls from individuals presenting distinct conformations in order to establish a typology: the criminal, the genius, the deviant, the madman… An individual could be assigned to a group based on a bump or hollow of their cranium. The era leant to toward systematisation; collecting and recording were employed to better understand the world. Beings and things were classified in order to understand and control them.

“Today we are doing more than merely consider introducing phrenology as a means of studying criminals. Several of the most distinguished juridical consultants have, without fully adopting the most radical views published on the topic, acknowledged it to have a degree of validity and truth that would suffice to justify more extensive and rational research. Perhaps examining the brains of the guilty, from assassins to the most ordinary thief, will eventually prove that there existed in these men a predictable tendency towards this or that crime, a result that would inevitably lead to restrictions in the severity of our laws.“

B. Appert, Bagnes, prisons et criminels, tome IV, 1836.

While this pseudoscience declined in popularity around the mid-century, it left a durable impression, particularly on novelists. Balzac, for instance, incorporated long descriptions of phrenological traits and associated them with each character’s personality.

“Mlle. Michonneau came noiselessly in, bowed to the rest of the party, and took her place beside the three women without saying a word.

“That old bat always makes me shudder,” said Bianchon in a low voice, indicating Mlle. Michonneau to Vautrin. “I have studied Gall’s system, and I am sure she has the bump of Judas.

Then you have seen a case before?” said Vautrin.

Who has not?” answered Bianchon.“

Honoré de Balzac, Le Père Goriot, 1835