One form of property confiscated from the clergy and aristocracy during the revolutionary period consisted of private libraries, which were temporarily stocked in vast ‘literary warehouses’ all over France. The tremendous numbers of items collected made it possible to create or enhance the libraries of major cities. However, as these institutions were neither large enough nor sufficiently organised to house all these works, many were sold quite cheaply. New connoisseurs of rare or precious books appeared, progressively giving shape to the figure of the bibliophile, a distinct social type of the 1830s.

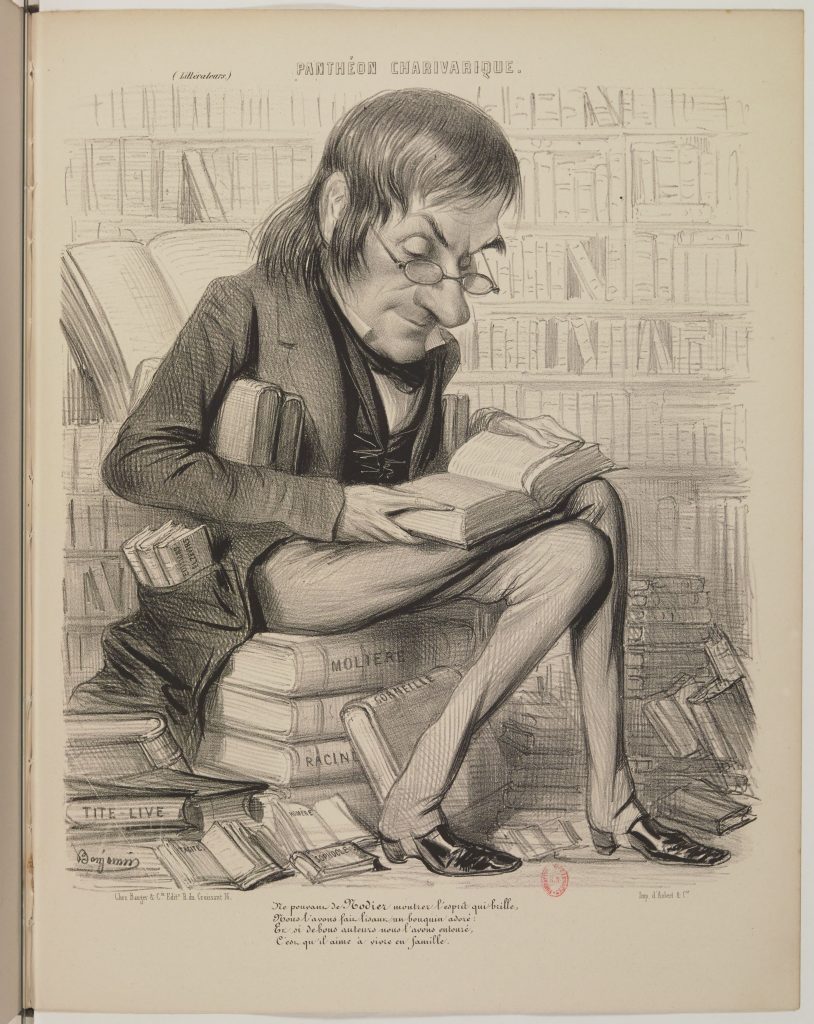

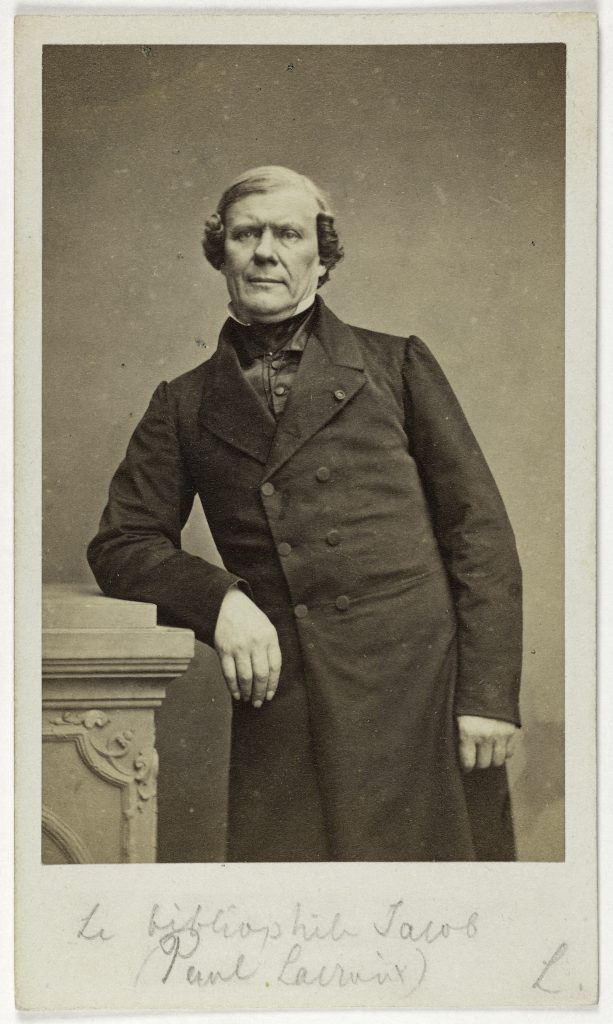

The sharpest of these bibliophiles, or ‘bibliomaniacs’ as they were called at the time, were highly attentive to the facture of these works (whether in terms of binding, typography, calligraphy or paper), they consider everything from provenance and condition to the rarity of the text, whether manuscript or printed. This was certainly true of Charles Nodier, who was a writer, bookseller and rare-book collector, and Paul Lacroix, known as ‘The bibliophile Jacob’, who promoted Old French just as people were rediscovering the Middle Ages. Balzac knew both of these bibliophiles, and himself possessed a select library of volumes, all of which he had bound with care.

‘I herewith return your invoice with the following indications as to their bindings. The symbol X […] signifies that a half-binding in Morocco leather is called for, while the symbol O means a half-binding in ordinary calfskin (do no more than remove the hair), both Xs and Os in red, as that is the only colour I have in my library.

Honoré de Balzac, Letter to Hippolyte Souverain, 15 January 1850