The gardens of Palais-Royal were subdivided shortly before the Revolution by the Duke d’Orleans who built houses with arcades around the periphery in addition to a theatre. The south side, facing the palace, was not completed due to lack of funds, and wooden shacks were put up there. Until the July Monarchy, numerous boutiques (several hundred of them!), restaurants and cafés, various theatres, gambling houses and prostitution attracted all kinds of foot traffic, strollers drawn to this neighbourhood of ill repute by its unbridled and flamboyant atmosphere. The wooden gallery was rebuilt in stone in 1829. After solicitation was forbidden in 1830 and the gambling houses closed in 1836, the gardens of Palais-Royal ceased to be the foremost site of entertainment for Parisians and tourists alike.

Between 1781 and 1784, the garden of the Palais-Royal remained practically unchanged. In 1787, the Duke d’Orleans had a vast edifice constructed, half sunk in the ground in the middle of the garden. Used for circus performances, it was destroyed by fire a dozen years later. The artist here depicts the garden in the morning, with a few strollers. The area was very much less crowded in the daytime than at night.

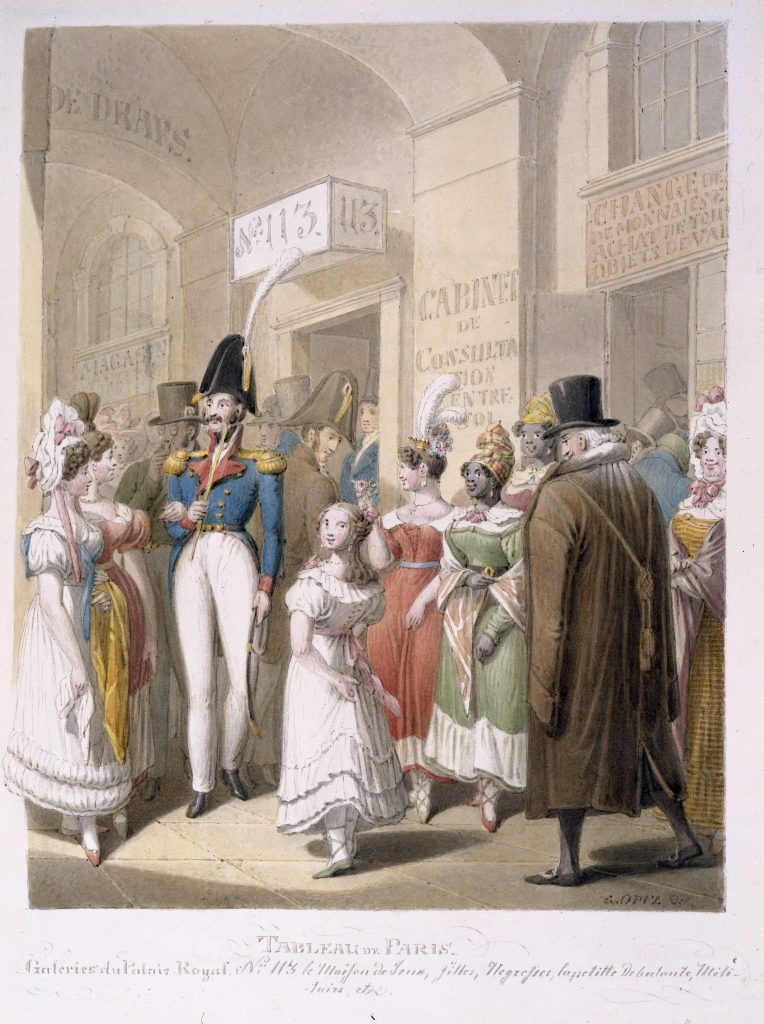

Georg Opiz drew a number of typical scenes of life around Palais-Royal. Among the many gambling houses, the 113, whose sign is visible, was the most famous. Prostitutes, distinguishable by their flashy clothes, parade under the galleries to meet up with businessmen, military officers or bourgeois looking for distractions, who all squeeze into this epicentre of Parisian playfulness.

As night falls and customers gradually depart the boutiques and cafés, they are replaced by creatures just as plentiful, but very different. This painting, which imitates an engraving (it reproduces a picture from the Salon of a few years prior) illustrates discussions between prostitutes and their clients.

Palais-Royal enjoyed enormous prestige in the minds of young Parisian students, who hoped to find answers there to their questions about women, and to appear mature by hanging out in ill-famed neighbourhoods. Félix de Vandenesse,the hero of Le Lys dans la vallée, recalls these youthful palpitations:

“But in Paris, and especially at this particular time, such talk among young lads was influenced by the oriental and sultanic atmosphere and customs of the Palais-Royal. The Palais-Royal was an Eldorado of love, where the ingots melted away in coin; there virgin doubts were over; there curiosity was appeased. The Palais-Royal and I were two asymptotes bearing one towards the other, yet unable to meet.“

Balzac, Le Lys dans la vallée, 1836 (translated by Katharine Prescott Wormely)

In Illusions perdues, Honoré de Balzac provided the most beautiful description of the Palais-Royal that has ever been. While he does not linger on the architecture, he does provide an incredibly poetic and precise analysis of the social function of this place, which had no equivalent in Paris.

“The Wooden Galleries of the Palais Royal used to be one of the most famous sights of Paris. Some description of the squalid bazar will not be out of place; for there are few men of forty who will not take an interest in recollections of a state of things which will seem incredible to a younger generation. The great dreary, spacious Galerie d’Orleans, that flowerless hothouse, as yet was not; the space upon which it now stands was covered with booths; or, to be more precise, with small, wooden dens, pervious to the weather, and dimly illuminated on the side of the court and the garden by borrowed lights styled windows by courtesy, but more like the filthiest arrangements for obscuring daylight to be found in little wineshops in the suburbs. The Galleries, parallel passages about twelve feet in height…The treacherous mud-heaps, the window-panes incrusted with deposits of dust and rain, the mean-looking hovels covered with ragged placards, the grimy unfinished walls, the general air of a compromise between a gypsy camp, the booths of a country fair, and the temporary structures that we in Paris build round about public monuments that remain unbuilt; the grotesque aspect of the mart as a whole was in keeping with the seething traffic of various kinds carried on within it; for here in this shameless, unblushing haunt, amid wild mirth and a babel of talk, an immense amount of business was transacted between the Revolution of 1789 and the Revolution of 1830. […] But the poetry of this terrible mart appeared in all its splendor at the close of the day. Women of the town, flocking in and out from the neighboring streets, were allowed to make a promenade of the Wooden Galleries. Thither came prostitutes from every quarter of Paris to “do the Palais.” The Stone Galleries belonged to privileged houses, which paid for the right of exposing women dressed like princesses under such and such an arch, or in the corresponding space of garden; but the Wooden Galleries were the common ground of women of the streets. This was the Palais, a word which used to signify the temple of prostitution. A woman might come and go, taking away her prey whithersoever seemed good to her. So great was the crowd attracted thither at night by the women, that it was impossible to move except at a slow pace, as in a procession or at a masked ball. Nobody objected to the slowness; it facilitated examination. […], until the very last moment, Paris came hither to walk up and down on the wooden planks laid over the cellars where men were at work on the new buildings; and when the squalid wooden erections were finally taken down, great and unanimous regret was felt.“

Balzac, Illusions perdues, 1843 (translated by Ellen Marriage)

The gambling houses were designated by number. They were tolerated by successive governments because of the large sums they brought in through licencing and taxes. Two of Balzac’s heroes come to try their luck at the Palais-Royal: in Le Père Goriot, Eugène de Rastignac wins 5,000 francs at n°9, while Raphaël de Valentin, from La Peau de chagrin, comes to lay down his last écuat n°36.

“Towards the end of the month of October 1829 a young man entered the Palais-Royal just as the gaming-houses opened, agreeably to the law which protects a passion by its very nature easily excisable. He mounted the staircase of one of the gambling hells distinguished by the number 36, without too much deliberation. […] If Spain has bull-fights, and Rome once had her gladiators, Paris waxes proud of her Palais-Royal, where the inevitable roulettes cause blood to flow in streams, and the public can have the pleasure of watching without fear of their feet slipping in it.Take a quiet peep at the arena. How bare it looks! The paper on the walls is greasy to the height of your head, there is nothing to bring one reviving thought. There is not so much as a nail for the convenience of suicides. The floor is worn and dirty. An oblong table stands in the middle of the room. […] There were several gamblers in the room already when the young man entered. Three bald-headed seniors were lounging round the green table. Imperturbable as diplomatists, those plaster-cast faces of theirs betokened blunted sensibilities, and hearts which had long forgotten how to throb, even when a woman’s dowry was the stake. A young Italian, olive-hued and dark-haired, sat at one end, with his elbows on the table, seeming to listen to the presentiments of luck that dictate a gambler’s “Yes” or “No.” The glow of fire and gold was on that southern face. Some seven or eight onlookers stood by way of an audience, awaiting a drama composed of the strokes of chance, the faces of the actors, the circulation of coin, and the motion of the croupier’s rake.”

Honoré de Balzac, La Peau de chagrin, 1830 (translated by Ellen Marriage)