At the beginning of the 19th century, the novel was considered an inferior genre, a vehicle for frivolous stories that a serious man would not include in his library—which would instead be reserved for works of history, politics or economics. The novel was accused of instilling depraved ideas in young people—it is these sentimental stories that make Emma Bovary dream, and lead her to reject her too ordinary life. When Balzac used the novel to propose a truly in-depth study of social relations, his project remained misunderstood for a long time. He was never admitted the Académie Française, which only went on to accept novelists in the second half of the century.

“The danger of novels and bad books is even more prevalent for young girls, because these despicable publications are now everywhere. Oh how many sins, how many deplorable downfalls, how many scandals, have been caused by a recklessly opened book!

A virgin who would expose herself to such dangers would be almost certain to succumb to them, to lose her innocence one day or another, not to mention the very serious misconduct that results from reading of this kind. More taste for prayer, the sacraments, holy things. The burning imagination, troubled by a thousand ghosts, worry in the heart, the demon at the door: this is the ordinary fruit of these unworthy books […]

No theatre, no novels, if we want to remain pure.“

Carlo Paterniani, La sainte Virginité, ou les Grands biens du trésor caché, Paris, R. Ruffet, 1864.

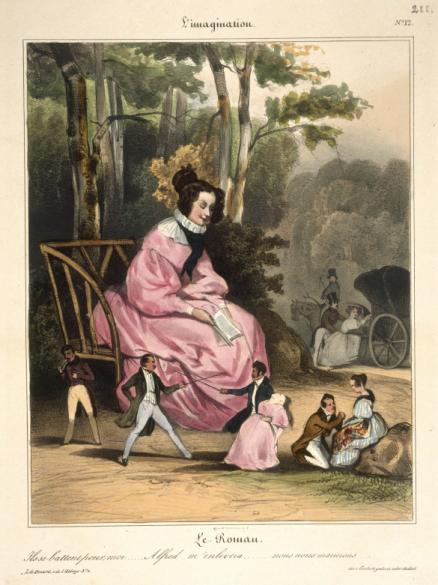

The fact that literature makes it possible to escape the monotony of daily life did not escaped artists. Daumier dedicated one of the engravings in his series l’imagination to the novel.

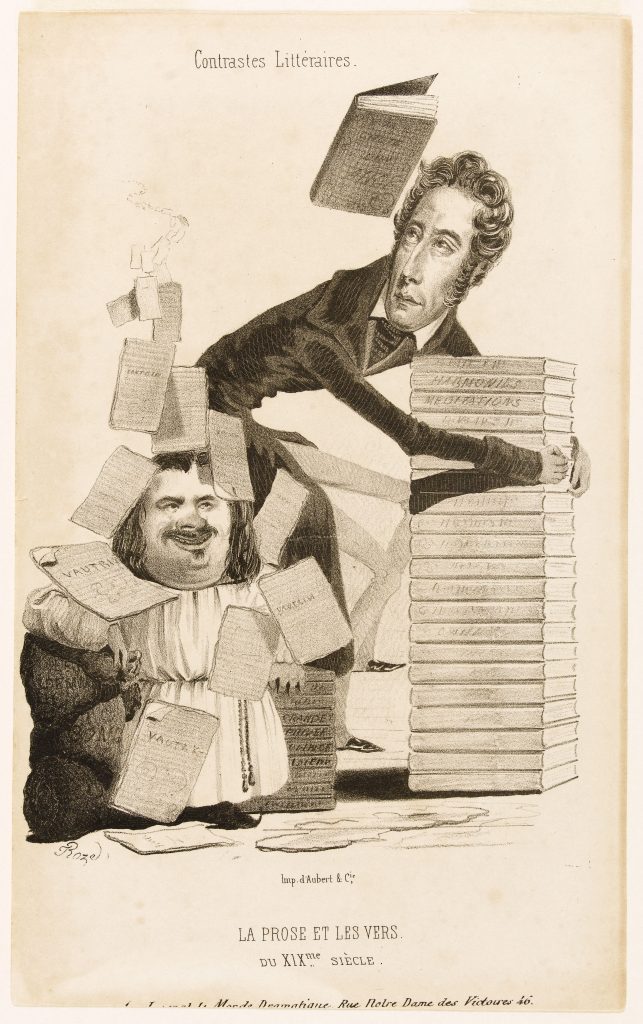

Tall, slim, with eyes looking to the sky in search of inspiration, the poet Alphonse de Lamartine, leans against his works (we can recognise Les Méditations poétiques, Les Harmonies poétiques et religieuses and La Chute d’un ange), offers a particularly striking contrast with Balzac at his feet, small and fat with a happy face. Balzac leans with one hand on bags stuffed with the mail sent to him by thirty-year-old women, and with the other hand on his works (the words ‘Grandet’, ‘work’, ‘stage’ can be read on the spines of the books). This caricature shows that Balzac, to most of his contemporaries, was the very type of novelist whose prosaic writing contrasts with the poet’s lyrical flights of fervour: the analytical value of his work is not understood.

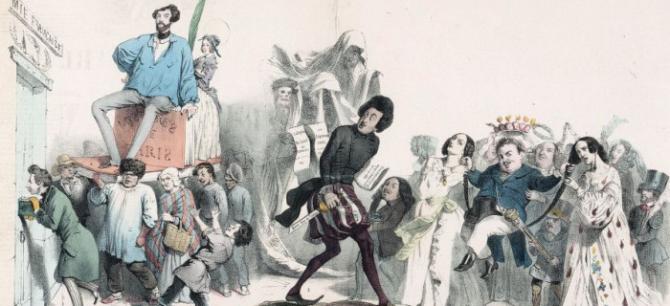

This engraving shows four great authors trying to enter the Académie Française, the ultimate achievement for writers. In front of the door waits poet Alfred de Vigny, followed by Victor Hugo dressed as a literary pope with a feather for a crosier and Notre-Dame de Paris, the cathedral that lent its name as the title of his most famous novel, as a tiara. Then comes Alexandre Dumas, recognisable by his dark complexion, fleeing from the ghosts of the writers who pursue him claiming their manuscripts—an allusion to the author’s borrowings from the great works of literature. Following him is Balzac, supported and crowned by women aged forty and older (from the novel A Woman of Thirty) and conquering the hearts to which he had found the key. The two poets, Victor Hugo and Alfred de Vigny, were ultimately admitted to the Académie Française, whereas the novelists Balzac and Dumas never were.