It was fairly common in the 19th century for men of the urban bourgeoisie to remain single. Custom made it easy to be sexually active outside of marriage: prostitution, by and large considered socially acceptable, was helped by low wages that made it difficult for working girls to make ends meet; the clear social chasm between master and servants facilitated dalliance with household help; and lastly, adultery was given a boost by the suppression of divorce from 1816 to 1884, concurrent with the upholding of the marriage of convenience. The bachelor and, most especially, the ageing bachelor, became favoured targets among writers and cartoonists.

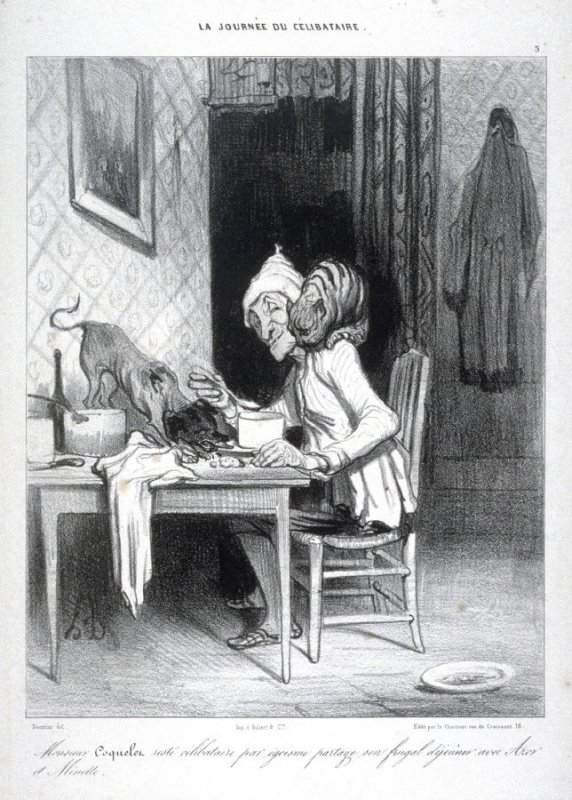

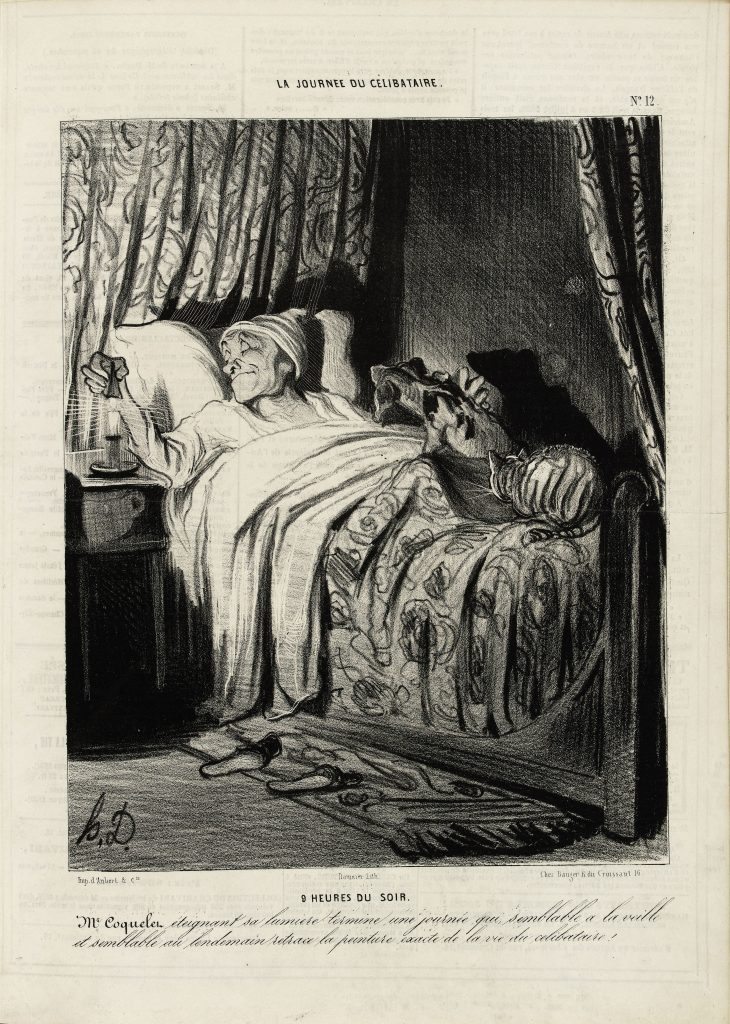

The aging bachelor is considered an egotistical hedonist when he is single by choice. However, those unable to establish a family for lack of means are presented as pernickety loners whose affective lives are limited to tending their cats, finches or potted plants! A few of these characters, like Daumier’s ‘Mr Coquelet’ caricature, combine egotism, meanness and obsessive compulsion.

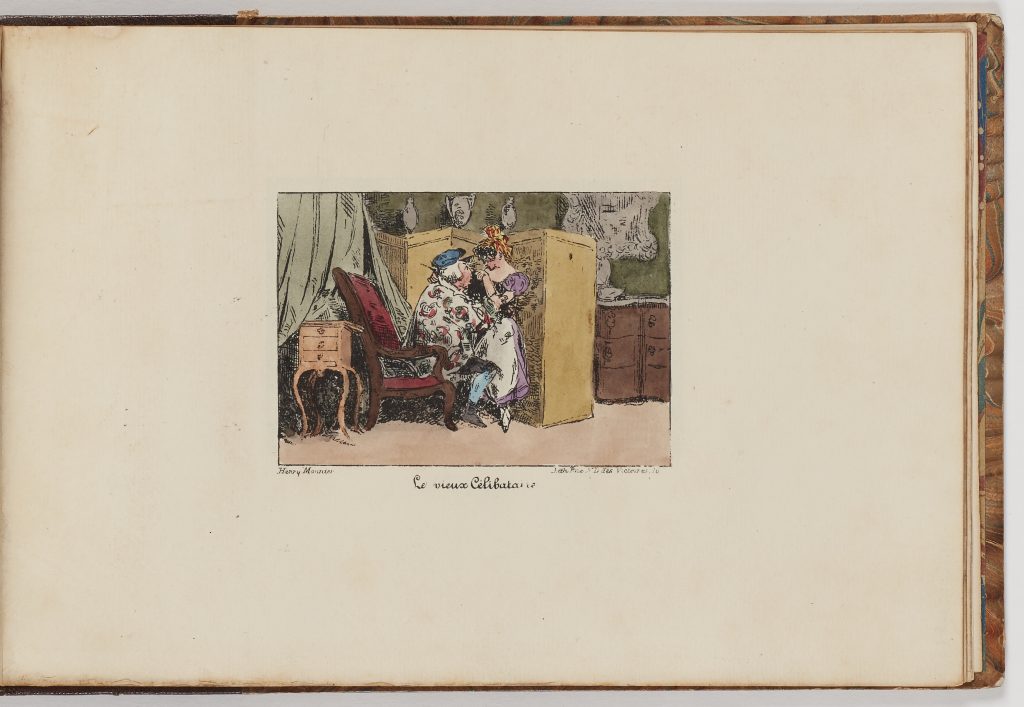

The songwriter Pierre Jean Béranger was tremendously popular during the Restauration and the July Monarchy; his lively, poetic compositions, sometimes with liberal or patriotic themes, set to simple and varied tunes, were as much a mainstay in the countryside as in goguettes (singing societies) or bourgeois drawing rooms. ‘Le vieux célibataire’, here illustrated by Henry Monnier, quite explicitly describes the seduction of a young serving girl by her bachelor master.

“My little maid, so irritatingly pretty

You ought to lend this old bachelor a hand,

Your master long did foolish things

For faces far less sweet than yours

[…]

But think on it; I’m writing out my will.

Be docile at last and yield to my

Kisses, the breast that has seduced me so.

Come on, Babet, indulge me just a bit,

Ah! You surrender, you succumb to my flame!

But nature, alas, betrays my heart’s desire

Don’t cry, come now, you’ll be my wife,

Despite my age and the mockery of many.”

The decisive factor pushing a young bachelor to marriage lay less in the charms of his future spouse than the fortune she brought to the altar, if this print by Victor Adam is to be believed. The series Un an de la vie d’un jeune homme (A year in the life of a young man) describes the joys of bachelorhood (gambling, dandyism, seduction, friendship), but also its perils (debts, STDs…). Marriage to a wealthy old lady puts an end to the young man’s shenanigans and transforms the condition of our young bachelor, who thus becomes an ‘established man’.