Though a world without internet, satellites or mobile phones, the 19thcentury was nonetheless a connected one. News circulated and was exchanged amongst people despite the distance separating them.

For one thing, there was correspondence. The French wrote a great deal, and their letters went abroad easily thanks to the malle-poste (mail coach), established shortly after the French Revolution. This rapid, horse-drawn coach was in charge of transporting despatches and mail. Letters arrived at the country’s 1,300 or so relay points. By 1830, even the countryside received coverage—a postman delivered the mail every other day. The envelopes, however, were as yet without stamps! An English invention, it was only in 1849 that stamps would make their appearance in France, depicting, not Marianne, but Ceres, goddess of the harvest—as befits a rural country.

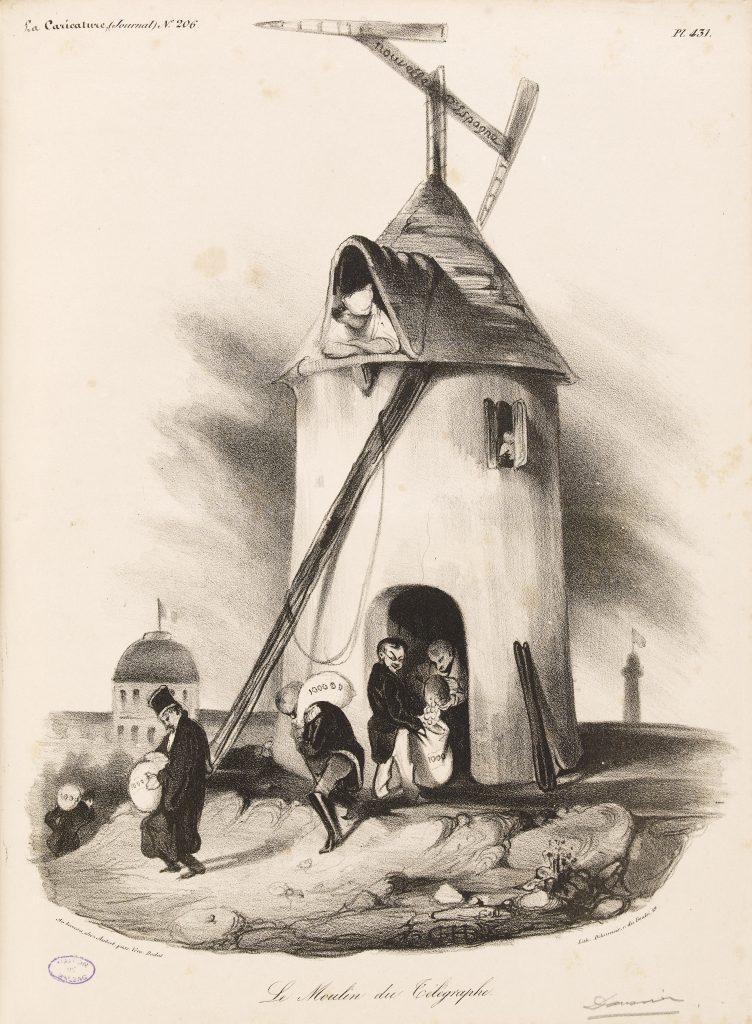

Progress surged ahead briskly. In 1794, the Chappe brothers invented the optical telegraph. A piece of news now took just nine minutes to go from Paris to Lille, thanks to the signal towers so brilliantly described by Alexandre Dumas.

Inventions came and went until the appearance of electrical telegraph transmission. In the mid-19thcentury, the American Samuel Morse had the first transnational cable lines installed. It was an immediate success and the network grew quickly. In the year of Balzac’s death, the telegraph became a public utility and the French adopted that ancestor of the SMS: the telegram.

“Yes, indeed, the very thing: a telegraph.Often, at the end of a road, on a hilltop, in the sunshine, I have seen those folding black arms extended like the legs of some giant beetle, and I promise you, never have I contemplated them without emotion, thinking that those bizarre signals so accurately travelling through the air, carrying the unknown wishes of a man sitting behind one table to another man sitting at the far end of the line behind another table, three hundred leagues away, were written against the greyness of the clouds or the blue of the sky by the sole will of that all-powerful master. Then I have thought of genies, sylphs, gnomes and other occult forces, and laughed. Never did I wish to go over and examine these great insects with their white bellies and slender black legs, because I was afraid that under their stone wings I would find the human genie, cramped, pedantic, stuffed with arcane science and sorcery. Then, one fine morning, I discovered that the motor that drives every telegraph is a poor devil of a clerk who earns twelve hundred francs a year and – instead of watching the sky like an astronomer, or the water like a fisherman, or the landscape like an idler – spends the whole day staring at the insect with the white belly and black legs that corresponds to his own and is sited some four or five leagues away. At this, I became curious to study this living chrysalis from close up and to watch the dumbshow that it offers from the bottom of its shell to that other chrysalis, by pulling bits of string one after the other.“

Alexandre Dumas, The Count of Monte-Cristo, 1846 (Translation Robin Buss).