Balzac imagines and constructs himself as a dandy through the refinement and precious character of his surroundings—both the works of art and decorations he acquired and his choices of clothing or accessories from the most renowned clothiers. He unabashedly projected himself in this emblematic figure, developed in his oeuvre through a number of characters and where at least three types may be distinguished. The dandy is above all a literary hero. Words are his weapon. The first type—which is the most attractive and also the most moving—is embodied by Rubempré and is a particularly literary dandy, as he fancies himself a writer. The penniless son of a shopkeeper and a déclassée mother, striking in his physical appearance and blessed with an unquestionable cultivated intelligence, he lacks only what he dreams of. A beautiful object in a luxurious setting he is unable to let go of, he draws on his innocent and naïve charm to get by, borrowing from a mentor the energy, the gold, and the tricks that will transform him beyond his capacities and ultimately kill him.

The second type is that of Rastignac. He comes from an old provincial noble family with no unsuitable relatives but with no fortune. He is the least dandy of the three because the most realistic, hardened as he is by his clear understanding and his will to succeed. His indefectible ambition to escape his unfavourable circumstances unfailingly motivates him and keeps him from straying from his goal through frivolity or sentimentality. Like Rubempré, he knows that appearance is everything , or almost, in the brilliant world where he wishes to belong, and that having the means and savvy to shine through unparalleled attire is crucial. Fashion, which is merely an extension of the person wearing it, is inherently the purview of the few due to the costs it entails. The dandy must therefore ensure his affluence by any means. He is an apparition, a flash of light, the brilliance of an expert who, vampirically consumes his world, drawing from it his subsistence, his substance and his power.

The last and most perfect type is that of Marsay. He possesses—or avoids—every quality as needed to embody this figure. Immensely rich, a necessary condition for shaping oneself at will and gliding over the fatal realities of a world he may ignore or acknowledge as he pleases, he is the very model of the social lion, brilliant and dominant. He fully commands and embraces Establishment codes. Without being fooled by it, he upholds the social order, the better to take advantage of it, making it a stage or a step-stool, a pedestal, one might say, for his extraordinary existence. Aristocratic in all things, from the breathe he exhales to the heel of his boots, he maintains a subtle balance between feminine refinement and inflexible masculinity. All this draped in the irresistible charm of an inalterable sweetness that never reveals his heart. As a man of impeccable taste, he knows how to change masks just in time to make an exit and live on.

Histoire des Treize. III La Fille aux yeux d’or

La Comédie humaine. Œuvres complètes de M. de Balzac

Paris : chez Furne, Dubochet et Cie, Hetzel et Paulin, 1843

9ème volume, tome I des Scènes de la vie parisienne

CHAPTER I: PARISIAN TYPES

“Lord Dudley [de Marsay’s father] was no more troubled about his offspring than was the mother,—the speedy infidelity of a young girl he had ardently loved gave him, perhaps, a sort of aversion for all that issued from her. Moreover, fathers can, perhaps, only love the children with whom they are fully acquainted, a social belief of the utmost importance for the peace of families, which should be held by all the celibate, proving as it does that paternity is a sentiment nourished artificially by woman, custom, and the law. Poor Henri de Marsay knew no other father than that one of the two who was not compelled to be one. The paternity of M. de Marsay was naturally most incomplete. In the natural order, it is but for a few fleeting instants that children have a father, and M. de Marsay imitated nature. The worthy man would not have sold his name had he been free from vices. Thus he squandered without remorse in gambling hells, and drank elsewhere, the few dividends which the National Treasury paid to its bondholders. Then he handed over the child to an aged sister, a Demoiselle de Marsay, who took much care of him, and provided him, out of the meagre sum allowed by her brother, with a tutor, an abbe without a farthing, who took the measure of the youth’s future, and determined to pay himself out of the hundred thousand livres for the care given to his pupil, for whom he conceived an affection.

[…] is not the Church the mother of orphans? The pupil was responsive to so much care. The worthy priest died in 1812, a bishop, with the satisfaction of having left in this world a child whose heart and mind were so well moulded that he could outwit a man of forty. Who would have expected to have found a heart of bronze, a brain of steel, beneath external traits as seductive as ever the old painters, those naive artists, had given to the serpent in the terrestrial paradise? Nor was that all. In addition, the good-natured prelate had procured for the child of his choice certain acquaintances in the best Parisian society, which might equal in value, in the young man’s hand, another hundred thousand invested livres. In fine, this priest, vicious but politic, sceptical yet learned, treacherous yet amiable, weak in appearance yet as vigorous physically as intellectually, was so genuinely useful to his pupil, so complacent to his vices, so fine a calculator of all kinds of strength, so profound when it was needful to make some human reckoning, so youthful at table, at Frascati, at—I know not where, that the grateful Henri de Marsay was hardly moved at aught in 1814, except when he looked at the portrait of his beloved bishop, the only personal possession which the prelate had been able to bequeath him, that admirable type of the men whose genius will preserve the Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman Church […]

Towards the end of 1814, then, Henri de Marsay had no sentiment of obligation in the world, and was as free as an unmated bird. Although he had lived twenty-two years he appeared to be barely seventeen. As a rule the most fastidious of his rivals considered him to be the prettiest youth in Paris. From his father, Lord Dudley, he had derived a pair of the most amorously deceiving blue eyes; from his mother the bushiest of black hair, from both pure blood, the skin of a young girl, a gentle and modest expression, a refined and aristocratic figure, and beautiful hands. For a woman, to see him was to lose her head for him; do you understand? To conceive one of those desires which eat the heart, which are forgotten because of the impossibility of satisfying them, because women in Paris are commonly without tenacity. Few of them say to themselves, after the fashion of men, the “Je Maintiendrai,” of the House of Orange.

Underneath this fresh young life, and in spite of the limpid springs in his eyes, Henri had a lion’s courage, a monkey’s agility. He could cut a ball in half at ten paces on the blade of a knife; he rode his horse in a way that made you realize the fable of the Centaur; drove a four-in-hand with grace; was as light as a cherub and quiet as a lamb, but knew how to beat a townsman at the terrible game of savate or cudgels; moreover, he played the piano in a fashion which would have enabled him to become an artist should he fall on calamity, and owned a voice which would have been worth to Barbaja fifty thousand francs a season. Alas, that all these fine qualities, these pretty faults, were tarnished by one abominable vice: he believed neither in man nor woman, God nor Devil. Capricious nature had commenced by endowing him, a priest had completed the work.

Honoré de Balzac, Illusions perdues, 1843 (Translation Ellen Marriage)

Illusions perdues – Troisieme partie : Eve et David

La Comédie humaine. Œuvres complètes de M. de Balzac

Paris : chez Furne, Dubochet et Cie, Hetzel et Paulin, 1843

8ème volume Etudes de moeurs, tome IV des Scènes de la vie de province (La Comédie humaine. Œuvres complètes de M. de Balzac

“Young M. de Rastignac had come to spend a few days with his family. He had spoken of Lucien in terms that set Paris gossip circulating in Angouleme, till at last it reached the journalist’s mother and sister. Eve went to Mme. de Rastignac, asked the favor of an interview with her son, spoke of all her fears, and asked him for the truth. In a moment Eve heard of her brother’s connection with the actress Coralie, of his duel with Michel Chrestien, arising out of his own treacherous behavior to Daniel d’Arthez; she received, in short, a version of Lucien’s history, colored by the personal feeling of a clever and envious dandy. Rastignac expressed sincere admiration for the abilities so terribly compromised, and a patriotic fear for the future of a native genius; spite and jealousy masqueraded as pity and friendliness. He spoke of Lucien’s blunders. It seemed that Lucien had forfeited the favor of a very great person, and that a patent conferring the right to bear the name and arms of Rubempre had actually been made out and subsequently torn up.

If your brother, madame, had been well advised, he would have been on the way to honors, and Mme. de Bargeton’s husband by this time; but what can you expect? He deserted her and insulted her. She is now Mme. la Comtesse Sixte du Chatelet, to her own great regret, for she loved Lucien.

“Is it possible!” exclaimed Mme. Sechard.

Your brother is like a young eagle, blinded by the first rays of glory and luxury. When an eagle falls, who can tell how far he may sink before he drops to the bottom of some precipice? The fall of a great man is always proportionately great.

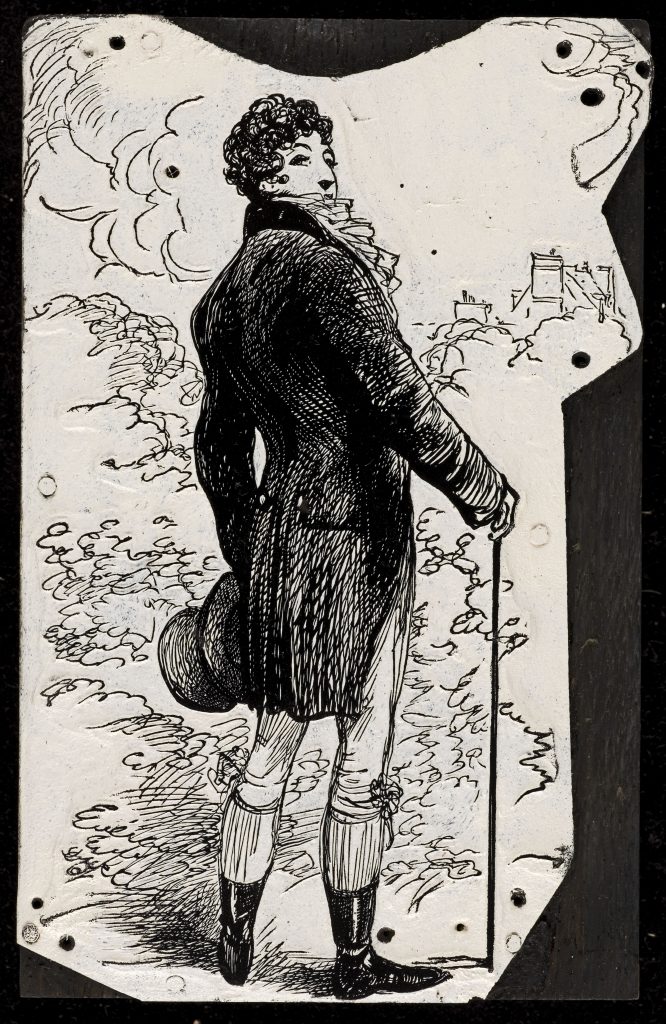

[…] Lucien had come to be the lion of the evening; he was said to be so handsome, so much changed, so wonderful, that every well-born woman in Angouleme was curious to see him again. Following the fashion of the transition period between the eighteenth century breeches and the vulgar costume of the present day, he wore tight-fitting black trousers. Men still showed their figures in those days, to the utter despair of lean, clumsily-made mortals; and Lucien was an Apollo. The open-work gray silk stockings, the neat shoes, and the black satin waistcoat were scrupulously drawn over his person, and seemed to cling to him. His forehead looked the whiter by contrast with the thick, bright curls that rose above it with studied grace. The proud eyes were radiant. The hands, small as a woman’s, never showed to better advantage than when gloved. He had modeled himself upon de Marsay, the famous Parisian dandy, holding his hat and cane in one hand, and keeping the other free for the very occasional gestures which illustrated his talk. Lucien had quite intended to emulate the famous false modesty of those who bend their heads to pass beneath the Porte Saint-Denis, and to slip unobserved into the room; however, Petit-Claud, having but one friend, made him useful. He brought Lucien almost pompously through a crowded room to Mme. de Senonches. The poet heard a murmur as he passed; not so very long ago that hum of voices would have turned his head, to-day he was quite different; he did not doubt that he himself was greater than this whole Olympus put together.