The domain of gastronomy was recognised late; also, the question of where to eat well, when it arose, applied only to Paris initially. Many restaurants did become famous: Véry, les Frères Provençaux and Le Café de Paris were well known, and novelists did not hesitate to set grand dinners in these locations; a few gastronomes consigned to paper fond memories of the hot quail pâtés with Malaga wine ‘worthy of the table of the gods’ that were served at the Rocher de Cancale, a restaurant frequented by the aristocracy of the Faubourg Saint-Germain. Other restaurants of variable quality were scattered around Paris. The cheapest served a clientele of workers and penniless students small meals whose only merit was to keep hunger at bay.

‘First class restaurants have, on the other hand, made notable progress: for the dinners that they once offered, there was a routine of cardboard and artificial flowers which they have shaken off, and their menus, now heightened by everything that could enhance them, have frankly entered into the habits of comfortable and elegant life. Apart from some obvious differences, we would not hesitate to class the dinners in the salons of our leading restauranteurs above the best tables in the city. A single example will serve to expose this truth to the light of day. It was at the Rocher de Cancale. One began with six little Marennes oysters and the same amount of soup, which neutralised the cold sensation of the oysters; one tried several soups, a glass of Madeira followed. The first course was worthy of the beginning. the narrator’s admiration is expressed in this way: ‘It is not that the number of dishes was so large; but their sequence was so well arranged, and the manner, the look, the freshness, the power and flavour were so excellent, that everyone had to admire them… We were served with English plated silverware of perfect taste, hot, and in the light of brilliant candles’. He mentions next some exquisite dishes, then exclaims ‘The rest of this small and magnificent dinner was perfect. If you want to have an idea of it, imagine M.de Talleyrand or Lorenzo de’ Medici giving a dinner for nine of his expertly food-conscious friends’.

Eugène Briffault, Paris à table, Paris, Hetzel, 1846

The Flicoteaux (student restaurant in the Latin Quarter) :

‘Flicoteaux’s restaurant is no banquet hall, with its refinements and luxuries; it is a workshop where suitable tools are provided, and everybody gets up and goes as soon as he has finished. The comings and goings within are swift. There is no dawdling among the waiters; they are all busy; every one of them is wanted. The fare is not very varied. The potato is a permanent institution; there might not be a single tuber left in Ireland, and prevailing dearth elsewhere, but you would still find potatoes at Flicoteaux’s. Not once in thirty years shall you miss its pale gold (the color beloved of Titian), sprinkled with chopped verdure; the potato enjoys a privilege that women might envy; such as you see it in 1814, so shall you find it in 1840. Mutton cutlets and fillet of beef are to Flicoteaux’s what black game and fillet of sturgeon at Véry’s; they are not on the regular bill of fare, that is, and must be ordered beforehand. Beef of the feminine gender there prevails; the young of the bovine species appears in all kinds of ingenious disguises. When the whiting and mackerel abound on our shores, they are likewise seen in large numbers at Flicoteaux’s; his whole establishment, indeed, is directly affected by the caprices of the season and the vicissitudes of French agriculture. By eating your dinners at Flicoteaux’s you learn a host of things of which the wealthy, the idle, and folk indifferent to the phases of Nature have no suspicion.’

Balzac, Illusions perdues, Paris, H. Souverain, 1839 (translation Project Gutenberg)

The widely spaced tables, the richness of the décor and the baskets of fruit at the centre of the room all indicate the opulence of this restaurant, where whole families would come to dine.

With the development of restaurants in the 19th century, various types of characters appeared to take advantage of free food, from the uninvited guest who joins the wedding feast to the trickster who refuses to pay his bill. Chiselling of this kind became a favourite subject of caricaturists. Here, Robert Macaire, Daumier’s incarnation of a master of small frauds and unscrupulous wheeler-dealer explains that he has forgotten his wallet and offers to leave his acolyte’s pitiful hat in lieu of payment.

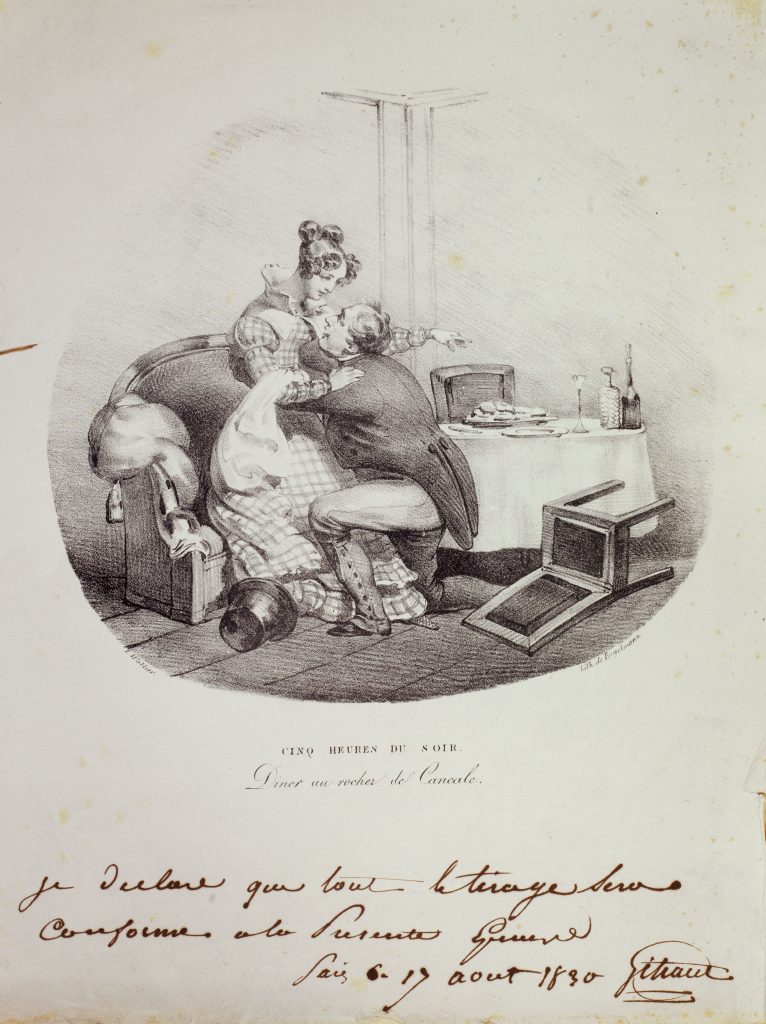

Certain restaurants offered their well-heeled clients private rooms with service on call. These rooms, away from public view and always provided with a large couch, fed all sorts of sexual fantasies, and they occupy an important place as much in the literature as in the imagery of the early 19th century. The draughtsman here evokes a scene of seduction at the Rocher de Cancale, one of the most famous establishments in Paris.