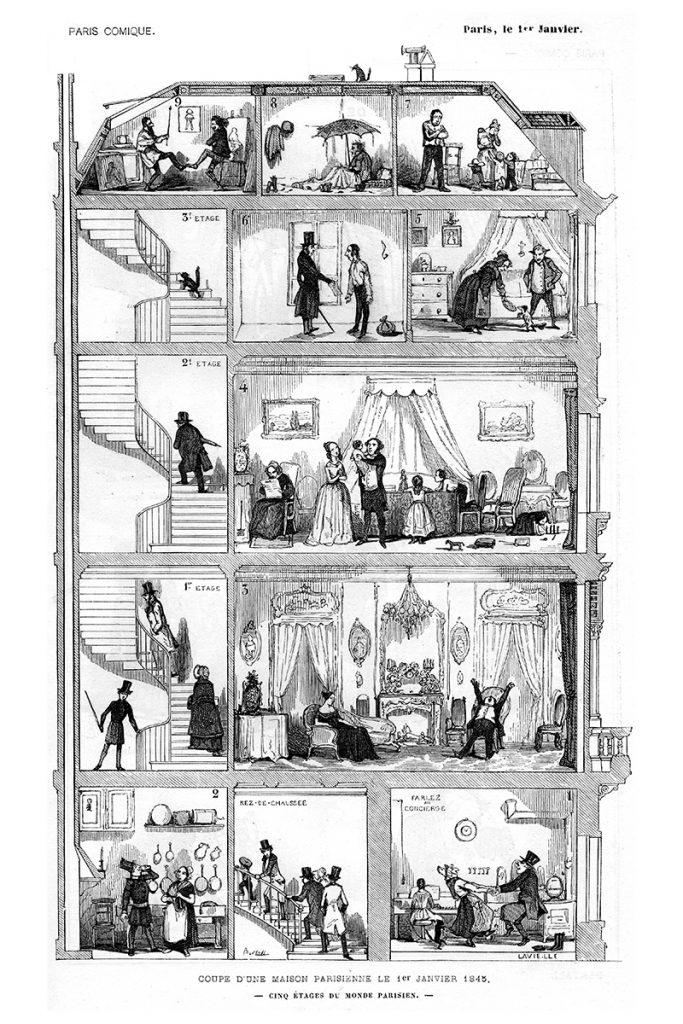

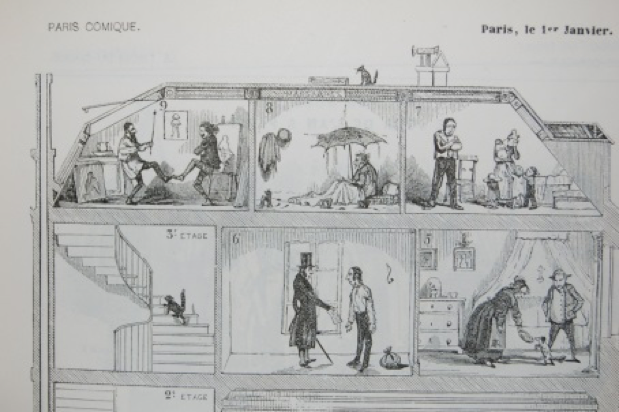

Living in Paris in the 19th century was not so simple. There was a great deal of new construction, but the large city also attracted large numbers of poor people looking for work. The wealthiest enjoyed sumptuous private mansions with large gardens, but most families lived in one or two rooms at the most. The most desirable apartments were to be found on the first floor and, as one went higher up, the economic status of the occupants decreased. This sociology of the floors in an apartment building was the subject of many comic representations.

“The best rooms in the house were on the first story, Mme. Vauquer herself occupying the least important, while the rest were let to a Mme. Couture, the widow of a commissary-general in the service of the Republic. With her lived Victorine Taillefer, a schoolgirl, to whom she filled the place of mother. These two ladies paid eighteen hundred francs a year.

The two sets of rooms on the second floor were respectively occupied by an old man named Poiret and a man of forty or thereabouts, the wearer of a black wig and dyed whiskers, who gave out that he was a retired merchant, and was addressed as M. Vautrin. Two of the four rooms on the third floor were also let—one to an elderly spinster, a Mlle. Michonneau, and the other to a retired manufacturer of vermicelli, Italian paste and starch, who allowed the others to address him as “Father Goriot.” The remaining rooms were allotted to various birds of passage, to impecunious students, who like “Father Goriot” and Mlle. Michonneau, could only muster forty-five francs a month to pay for their board and lodging. Mme. Vauquer had little desire for lodgers of this sort; they ate too much bread, and she only took them in default of better.

At that time one of the rooms was tenanted by a law student, a young man from the neighborhood of Angouleme, one of a large family who pinched and starved themselves to spare twelve hundred francs a year for him. […] Above the third story there was a garret where the linen was hung to dry, and a couple of attics. Christophe, the man-of-all-work, slept in one, and Sylvie, the stout cook, in the other.’

Honoré de Balzac, Le Père Goriot, 1834 (translated by Ellen Marriage)

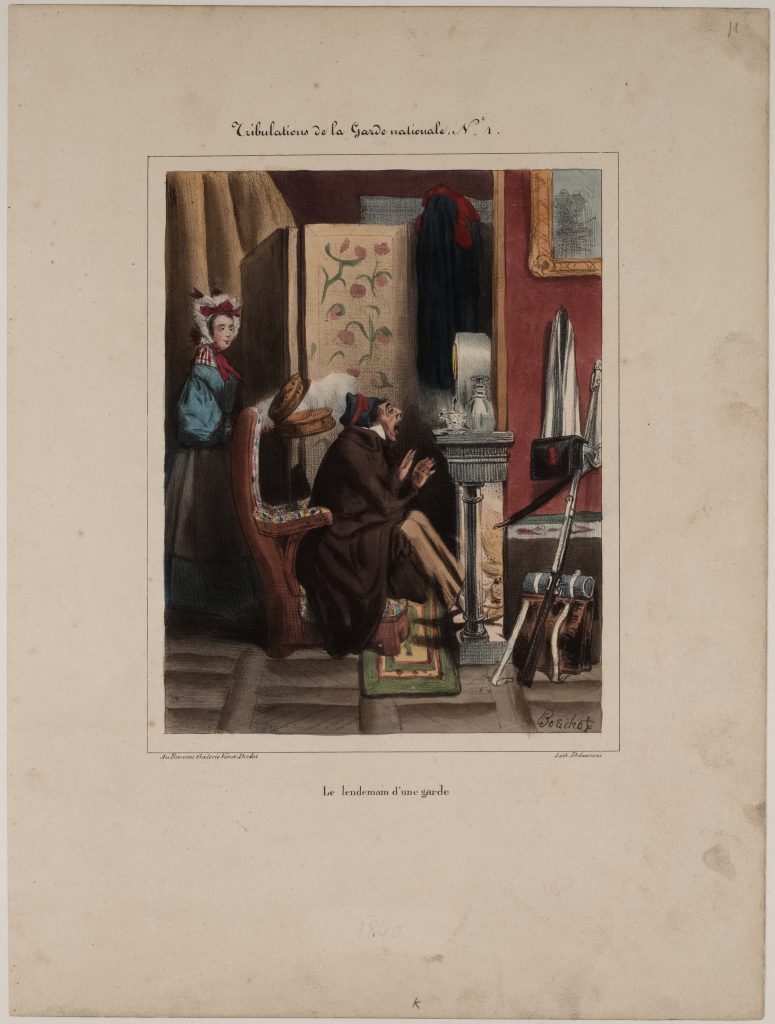

Painters were not very interested in depicting daily life at the beginning of the 19th century, and still in 1820 the subject was only found in genre scenes. It was not until the Realist movement in the second half of the century that painters began to represent to the Parisian interior. It was therefore draughtsmen who preserved the memory of these habitations during the reign of Louis-Philippe in their often humorous prints.

Space was as much a luxury as it is today, and the stacking of furniture and boxes, which it was the main purpose of wind-screens to hide, seems to have been widely practised in their apartments by the petty bourgeoisie.

‘Mademoiselle Leseigneur herself opened the door. On recognizing the young artist she bowed, and at the same time, with Parisian adroitness, and with the presence of mind that pride can lend, she turned round to shut the door in a glass partition through which Hippolyte might have caught sight of some linen hung by lines over patent ironing stoves, an old camp-bed, some wood-embers, charcoal, irons, a filter, the household crockery, and all the utensils familiar to a small household. Muslin curtains, fairly white, carefully screened this lumber-room—a capharnaum, as the French call such a domestic laboratory—which was lighted by windows looking out on a neighboring yard. Hippolyte, with the quick eye of an artist, saw the uses, the furniture, the general effect and condition of this first room, thus cut in half.

The more honorable half, which served both as ante-room and dining-room, was hung with an old salmon-rose-colored paper, with a flock border, the manufacture of Reveillon, no doubt; the holes and spots had been carefully touched over with wafers. Prints representing the battles of Alexander, by Lebrun, in frames with the gilding rubbed off were symmetrically arranged on the walls. In the middle stood a massive mahogany table, old-fashioned in shape, and worn at the edges. A small stove, whose thin straight pipe was scarcely visible, stood in front of the chimney-place, but the hearth was occupied by a cupboard. By a strange contrast the chairs showed some remains of former splendor; they were of carved mahogany, but the red morocco seats, the gilt nails and reeded backs, showed as many scars as an old sergeant of the Imperial Guard. This room did duty as a museum of certain objects, such as are never seen but in this kind of amphibious household; nameless objects with the stamp at once of luxury and penury’.

Honoré de Balzac, La Bourse, 1832 (translation by Clara Bell)