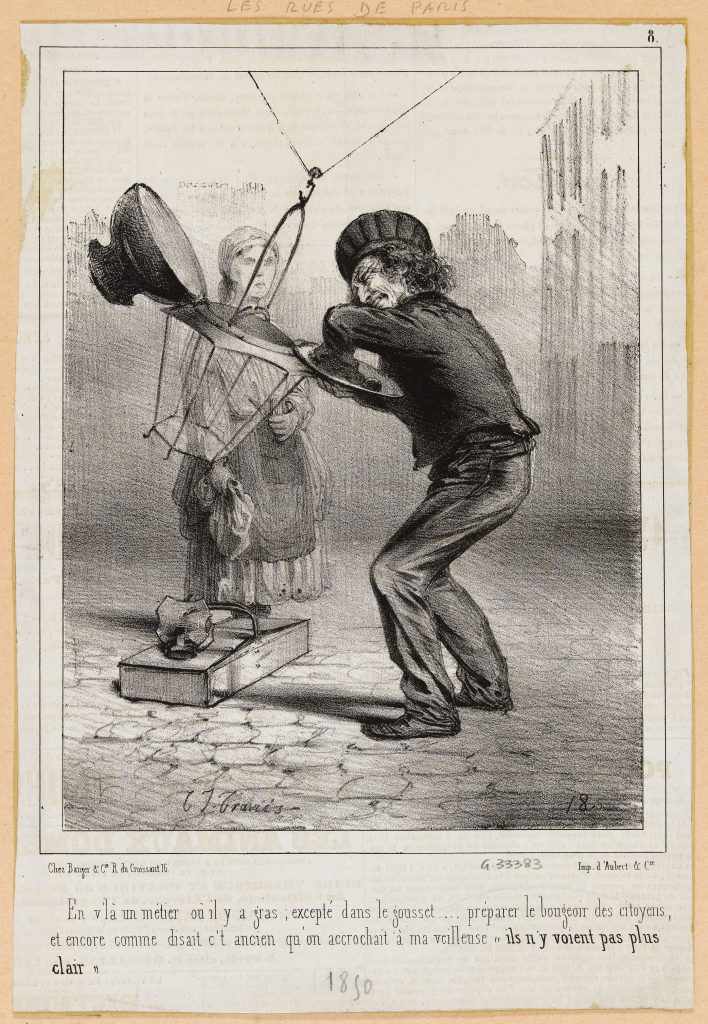

Hailing from London, gas-powered public lighting caused quite a stir in early 19th-century Paris. Dazzling and smelly, it elicited little fondness initially, although the invention undeniably constituted real progress. It must be said that the old oil lamps were, for the city’s 150 or so lighters of streetlamps, an opportunity for employment that required dexterity and skill. When the decision was made to run gas along the streets, they became gas-lighters. The gestures were simplified and mechanical. While a certain know-how was lost, the streets of Paris gained in safety by night.

“These narrow streets, dark and muddy, where trades are carried on which do not care about external appearance, take on at night a mysterious physiognomy and one full of contrasts. Coming from the bright lights of the rue Saint Honoré, the rue Neuve des Petits Champs and the rue de Richelieu, where there are always crowds and where are displayed the masterpieces of Industry, Fashion and the Arts, any man to whom Paris at night is unknown would be seized with gloom and terror as he plunged into the network of little streets which surround that brightness reflected in the sky itself. Thick shadow succeeds upon a torrent of gaslight. At wide intervals, a pale streetlamp casts its smoky and uncertain gleam, not seen at all in some of the blind alleys.“

Honoré de Balzac, Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes, 1838 (Translation Rayner Heppenstall)

For domestic interiors, the available sources of lighting were more varied. The wealthiest homes relied on wax tapers ensconced in magnificent chandeliers and lustres. Their beautiful white light glinted off the mirrors and gilding of bourgeois drawing rooms. But wax cost a fortune. Often, poor households had only tallow candles, which provided little light and gave off an unpleasant odour. Only slightly more effective, oil lamps were also toxic, as the fuels were suspect mixtures: rapeseed, walnut, hempseed and poppy, which often caused inflammations and headache.

“In front of the table was a commonplace desk-chair covered in red sheepskin faded with long use; six poor-quality chairs made up the rest of the furniture. On the mantelpiece Lucien noticed an old branched sconce of the kind used at the card-table, furnished with four wax candles and a shade. When Lucien, discerning all around him the symptoms of stark poverty, asked why he sued wax candles, d’Arthez replied that he could not bear the smell of burning tallow. This peculiarity indicated his very delicate physical sensitivity, which is also a sign of acute moral sensibility.“

Honoré de Balzac, Illusions Perdues, 1837. (Translation Herbert J Hunt)

Starting around 1850, petrol-lamps became extremely popular, and gas steadily made its way to ‘all floors’ of the capital’s buildings. The magic of electricity, however, would not cast its light in homes until the first days of the 20thcentury.