‘Calyste was therefore necessarily ignorant of modern literature, and the advance and present progress of the sciences. His education had been limited to geography and the circumspect history of a young ladies’ boarding-school, the Latin and Greek of seminaries, the literature of the dead languages, and to a very restricted choice of French writers.’

Honoré de Balzac, Béatrix, 1839 (Translation Katharine Prescott Wormeley)

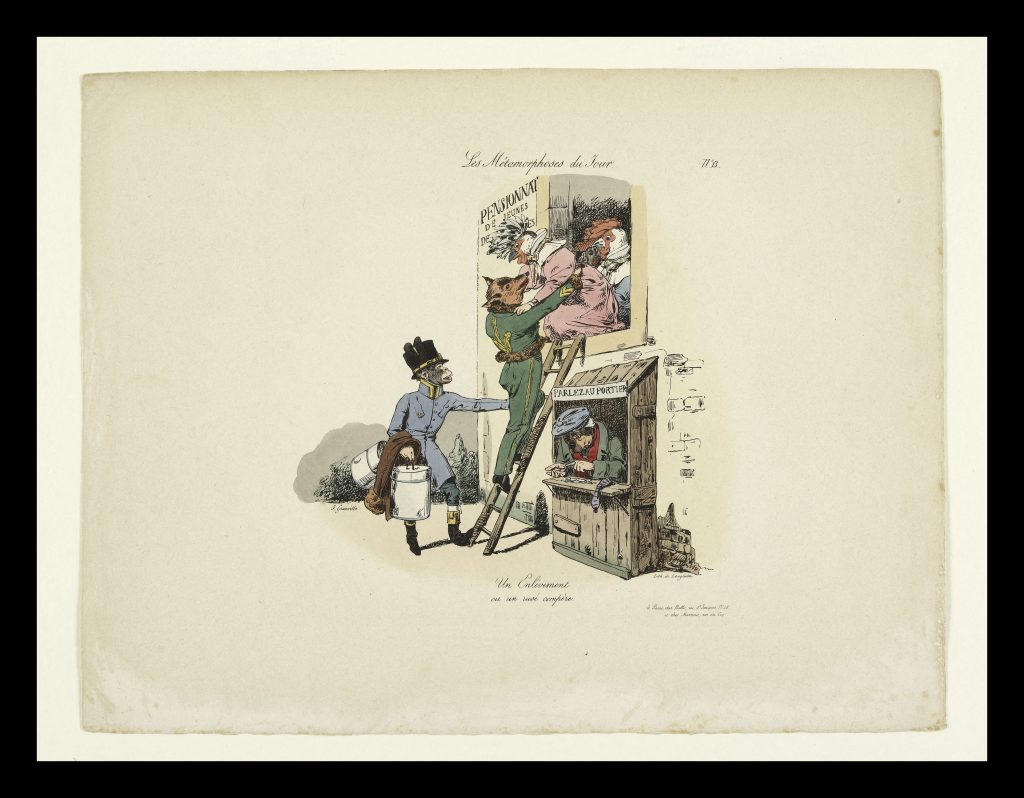

At the beginning of the 19th century, parents among the petite bourgeoisie of Paris and the Provinces entrusted their children to boarding schools, pensions and institutions. In the interval between the collegiate system of the Ancien Régime and creation of the so-called free establishments, they shouldered the role of dispensing secondary education.

Boys were housed in regulated dormitories where discipline might range from military rigour to a familial atmosphere. Classes and other training, whose curricula were not consistent, might take place outside the boarding house, which would, in such case only provide children with food and shelter. Balzac’s memories of these was tepid, in part because he spent his youthful years bouncing from one institution to another, rarely returning to the family home.

For girls, these institutions provided a substitute for the convents that were shuttered during the French Revolution. Future brides were given instruction in deportment and an extremely succinct course of studies.

‘These chemists had rather remarkable ideas: their idea of giving their daughter a good education was to send her to a boarding establishment.’

Honoré de Balzac, La Maison Nucingen, 1838.