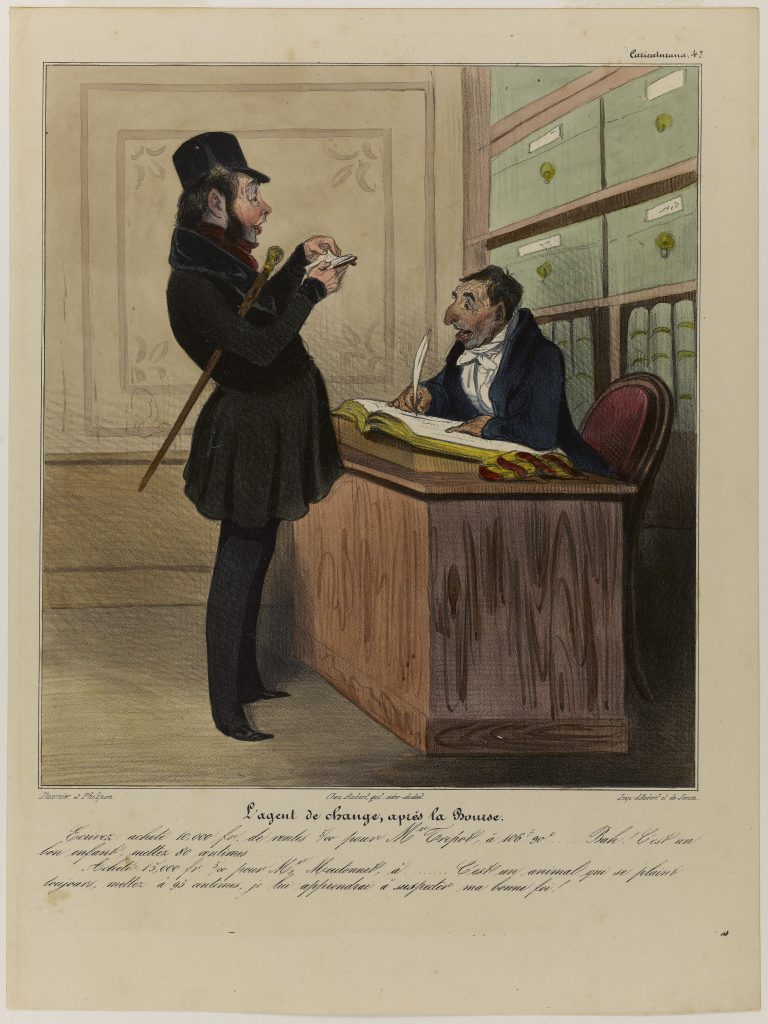

Speculation on the futures of industrial corporations became an inexhaustible source of jokes for caricature and humourists, who delighted in exposing the disappointment of naïve souls attracted by the prospect of easy wealth, and aptly fleeced by shady businessmen. Here, Daumier depicts an unscrupulous trader who changes the price of securities according to the client.

In his series, ‘Then and now’, Henry Monnier compares customs and habits of the Ancien Régime with those of his day. These two prints weigh the treatment of the bankrupt as being formerly pilloried and now housed in comfortable prisons where they enjoy fine dining in the company of attractive ladies. While bankruptcy was feared by honest businessmen, some speculators used it as a way to make a fortune at the expense of those who trusted them.

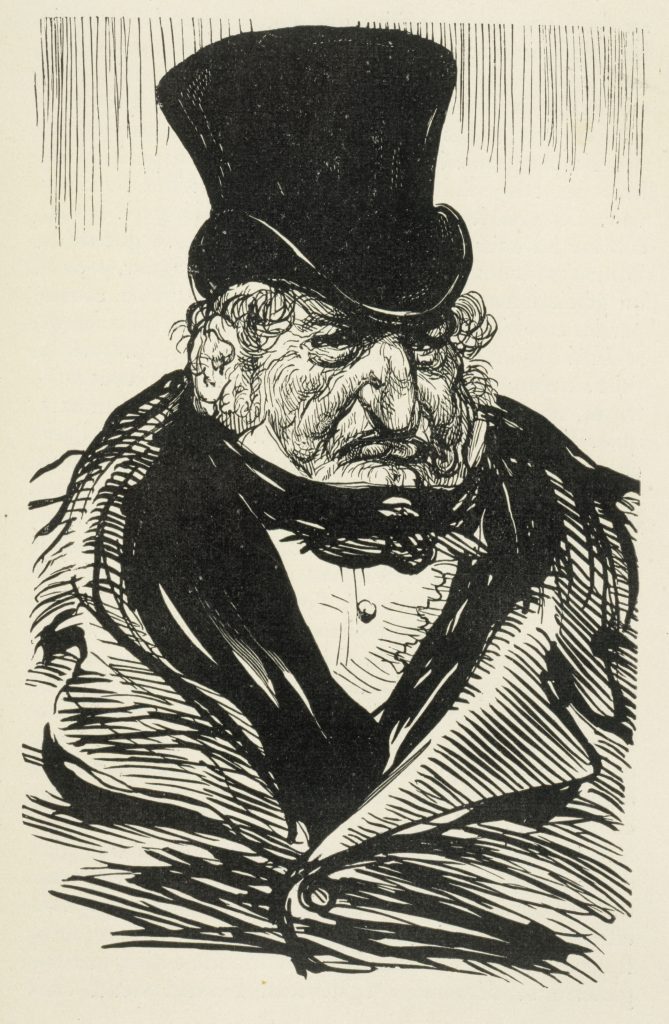

Nucingen, the lynx of finance, is one of the most complex characters in the entire Comédie humaine. The Alsatian banker amasses his fortune using liquidation as a tool, faking bankruptcy to buy back shares on the cheap. While Balzac was not conversant with all the subtleties of financial mechanisms, he understood quite well that fraudulent manoeuvres, if deftly managed, could well enrich their authors.

‘“Blondet has roughly given you the account of Nucingen’s first two suspensions of payment; now for the third, with full details.—After the peace of 1815, Nucingen grasped an idea which some of us only fully understood later, to wit, that capital is a power only when you are very much richer than other people. In his own mind, he was jealous of the Rothschilds. He had five million francs, he wanted ten. He knew a way to make thirty million with ten, while with five he could only make fifteen. So he made up his mind to operate a third suspension of payment. About that time, the great man hit on the idea of indemnifying his creditors with paper of purely fictitious value and keeping their coin. On the market, a great idea of this sort is not expressed in precisely this cut-and-dried way. Such an arrangement consists in giving a lot of grown-up children a small pie in exchange for a gold piece; and, like children of a smaller growth, they prefer the pie to the gold piece, not suspecting that they might have a couple of hundred pies for it.”’

Honoré de Balzac, La Maison Nucingen, 1838 (Translation James Waring)

Seized by the stock market frenzy, Balzac invested in Northern Railroad stocks the entire sum entrusted to him by his mistress, Madame Hanska, against the advice of his friend James de Rothschild. The stock price fell drastically, placing the novelist in a difficult position vis-à-vis his ‘full, white delight of love.’

“Just now, my Evelyn, our affairs are not going well. The drop in the North is frightening and inexplicable. Meanwhile, there is a note in England for a loan to Ireland, loans in Prussia and Austria. What’s to be done? Had I only sold at 742, I could buy at 690! See, 52 francs on 50 shares comes to a profit of 2,500 francs. I thought to leave, but for this I must be here to collect and stay alert and so on. Lest all our sheep burn to a crisp! Adieu for now, my full white delight of love…”

Honoré de Balzac, letter to Mme Hanska, 18 October 1846