The technical aspects of publishing underwent major changes at the beginning of the 19th century. Following an invention by Jean-Nicolas Robert in 1798, paper was no longer made ‘to measure’ on mesh frames of variable size, ranging from grand aigle to petit Jésus, but rather by machines that could extrude paper continuously. The Stanhope lever press, which made it possible to print sheets ‘in one go’, then mechanical printing press thrust printing into the industrial era. Woodcut prints, a technique rediscovered by the printmaker Thomas Bewick, made it possible to print finely drawn images in line with the text; thus an appreciation for vignettes edged out the taste for traditional ex-folio plates in the illustrated publications that took over booksellers’ shop windows.

These innovations profoundly transformed the appearance of books. The work, its cover often illustrated in order to attract buyers, was no longer comprised of booklets sewn together, but booklets directly attached to the broché volume. In order to make them easier to hold, publishers began to reduce the size of books, such as Charpentier, who launched the Chemins de fer imprint, sold in railroad stations and consisting of works that readers could easily carry about. These various elements contributed to the emergence of low-cost books, whose success was bolstered by the increasing numbers of readers. Balzac was well acquainted with all these innovations, not only as a writer, but as a ‘man of letters cast in lead’ as he liked to style himself (he was at one point a publisher, then a printer and later a typographer). Indeed, he made this the subject of one of his novels, Illusions perdues (Lost Illusions).

« Les dévorantes presses mécaniques ont aujourd’hui si bien fait oublier ce mécanisme [des presses à bras], auquel nous devons, malgré ses imperfections, les beaux livres des Elzevier, des Plantin, des Alde et des Didot, qu’il est nécessaire de mentionner les vieux outils auxquels Jérôme-Nicolas Séchard portait une superstitieuse affection ».

Honoré de Balzac, Illusions perdues, Paris : Furne, Dubochet, Hetzel et Paulin, 1843

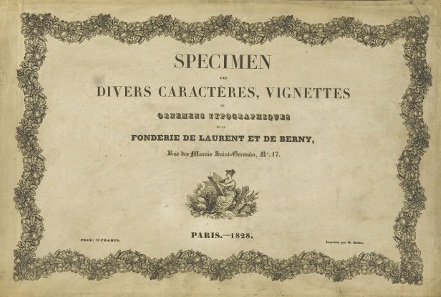

Balzac was successively a publisher, printer and then a typographer from 1826 to 1828. He printed this catalogue for potential clients to see the various typefaces, decorative elements and vignettes his printshop was capable of. His typographic material was both old (following his purchase of the workshop contents of the Gillé foundery, a famous 18th century firm) and modern (with vignettes specially created for his company by artists like Henry Monnier and Achille Devéria).

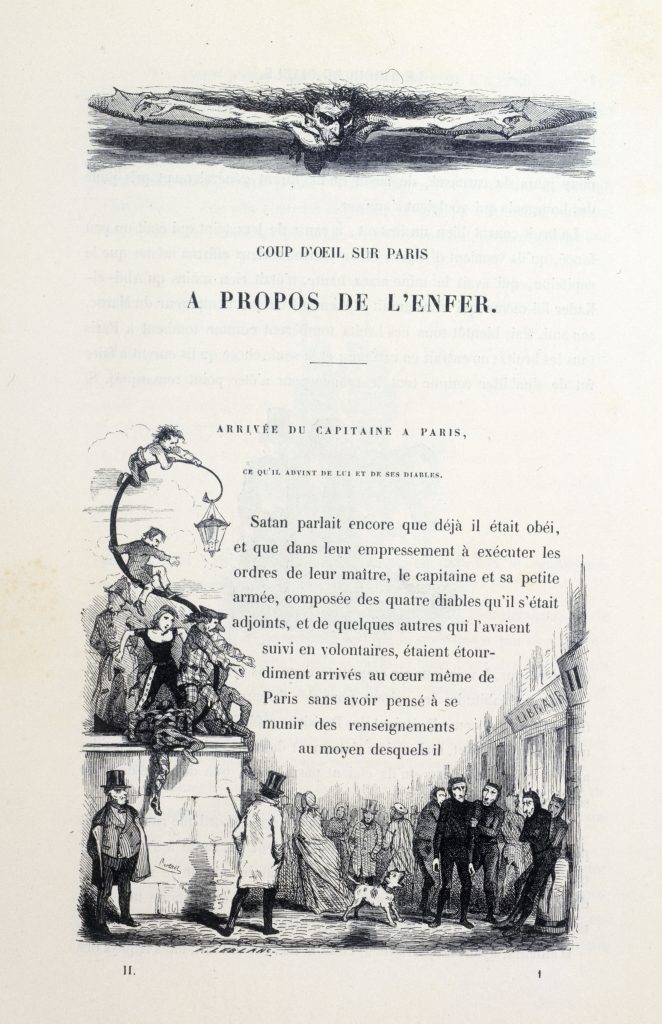

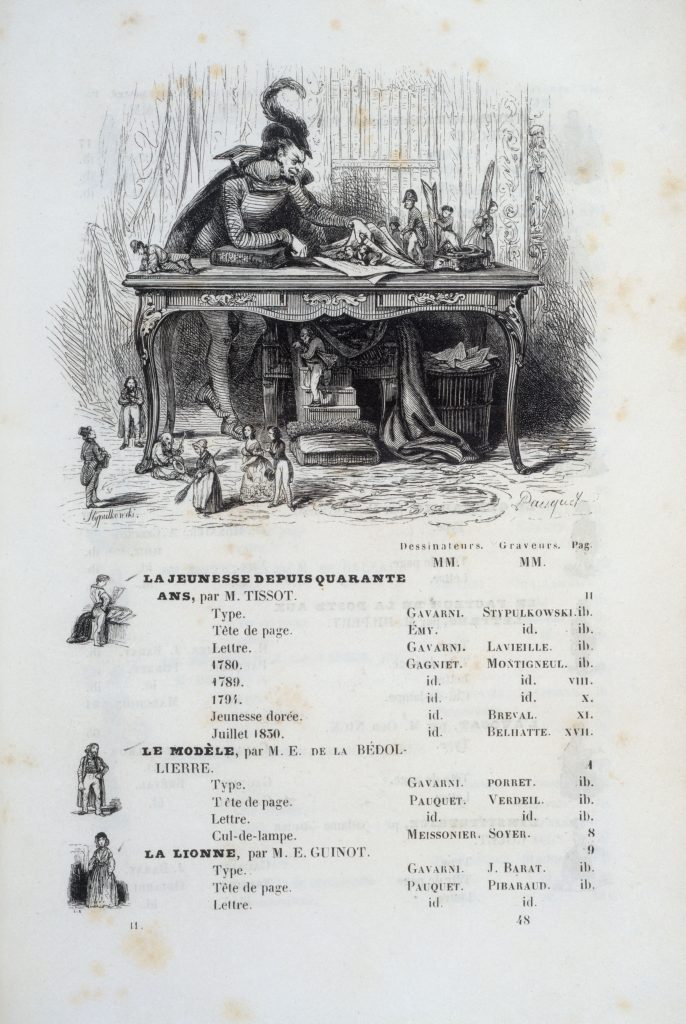

This work, abundantly illustrated with end-cut woodcuts was a tremendous publishing success. The illustrations, provided by the some of the period’s greatest artists (notably Henry Monnier, Grandville and Gavarni), were accorded great importance and listed in the table of contents.